After phone calls were made to check, Bradley took Pete and me in the quad bike over to see the other sheds.

We chugged up the dirt bank and out onto the wide dusty track, and we rocked around, Bradley going gently for Pete’s and my sake. It was warm and I drew as we went, past the homestead field and the actual homestead (Nana Willis worked here as a girl) and then down through the tea-trees to Johnny Wells’.

We passed people working, Tanya Maynard and her Angel, that seductive dog, and as Pete had said of himself before, I felt like a bit of a tourist, a bloody interloper, but John made us really welcome.

I sat, to draw Dingo and Yaron, squatting on a plastic drum in their plucking annex. I got used to them and they used to me. I drew Brandon in the gurry porch, where he was squeezing the bird oil into enormous drums, then flicking each bird through a small window of plastic strips to the next room for Dingo and Yaron to pluck. The birds are then sent into the next room where they’re cleaned and packaged after cooling, ready for sale.

Dingo and Yaron were watchful at first, wary of me. They warmed up when they knew that they could be themselves and that I knew a thing or two about birding; this is the thing you see, though I admit it was fully forty years ago, with Uncle Frank and Aunty Heather, and I have no idea for how long it lasted during that Easter break. But there, lying deep in the dirt that’s black when it’s wet, my shoulders to the hole, my hand down very low, the bird beak, the neck, hauling it out, I tried to kill it, like Frank taught me. But my wrist is too weak, so he says, stop, and to hand them all to him and he’ll do the quick kill. He squeezes them of their gurry into the 44-gallon drum on the back of tractor, and I can recall the sound of that squeeze, the sound of the finishing tap of the top of the bird’s head against the inside of the drum, and then the spit.

I watched Frank spit up the birds on the little ABC video made not long after I was there, and I heard that sound of the beak web, the bottom jaw, going down the smooth spit, whrorwaash, whrorwaash.

It was a great sound to hear again, because it placed me immediately back inside the tussocks.

There’s wind, and down there in the tussock in the hole it is warm. The warmth of the hole is quick to reach your hand and you know that it’s a bird and not a snake. I did feel a cold hole once and pulled my arm out sharply. Snake or not, I wasn’t going to test it.

Dingo came out from the shed as we were leaving Johnny’s and said, ‘How’re you goin’, see ya later Bradley’. I asked him if I could talk to him again and he says, ‘Yeah sure’. So Pete and I headed up to Burnie to interview him, months later. He’s a tall, strong Aboriginal man, a proud but gentle figure, and protective of his family, their future and the safety of their restorative traditions.

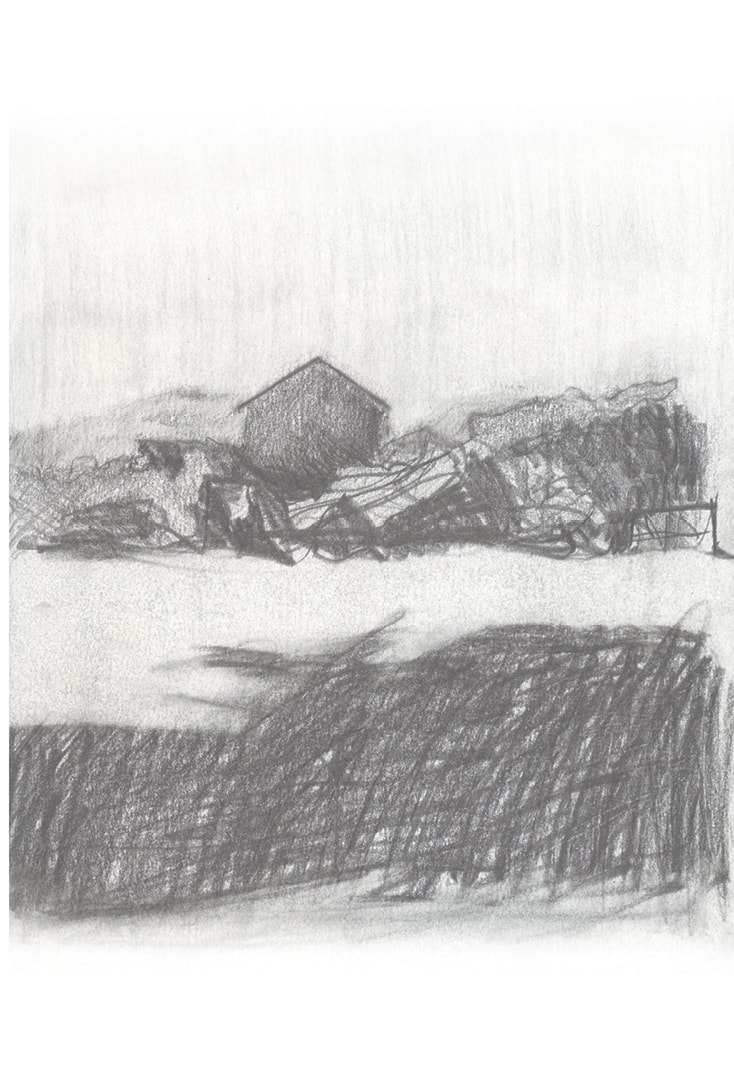

We quad further though the trees and out to the Vansittart side, east end of Big Dog, between Timmy Maynard’s sheds.

In the distance we see the sheds with an Aboriginal flag flying, that’s the Flinders Island Aboriginal Association, and that’s another matter, a place we haven’t made a connection with yet. I’d like to say howdy to them sometime, but it’s really none of my bloody business. For now, I’m lucky to be where I am at the east end, regardless. After we say our hellos to Timmy and I meet Bucky Brown, who knew my dad and Frank, and liked them, we are welcomed. We head back to the hut and Tara Maher puts their dog away so I can settle in for some drawing.

I last came here with Indigenous students and other teachers a couple of decades ago. I wandered off from them all, to walk back in the heat by myself to the homestead. I snuck in over the bare floor joists and sheep wool and webs to where naturalists had been leaving lists of birds on the walls. I had to follow my nose that day, recalling the drive around the place on Frank’s tractor when I was 17. The track was the same, the spaces and slopes of course, much the same. Back at the East End Hut though, now, I sat square on the granite foreground to draw, as a record of it, with its clutter and makeshift repairs, and mould and cigarette butts and the sun-warmed odour of men who slept there. It was earthy, and definitely not ours anymore, and no bother to me.

Timmy is a big bloke, not at all like the vandalised image of him on the Lady Barron foreshore walk. He looked across at me as we were leaving and said, ‘Come back anytime.’ This is pretty bloody special, so you bet I will.

On the way back we went up Bald Hill and Middle Hill. I want to be left on Bald Hill to photograph and draw for a while. I watch the quad bike chug away a bit, and enjoy the two soft figures, Bradley in his black hoodie, Pete and his beanie and soft ‘dun’ coat, on the rounded four-wheeler, among tussocks and brown dust.

This is where I want to place Joan, right back in her spot, in my portrayal of her. This is where the women, in my mind, really meet the wind.

I photographed places with Nana Willis’s camera, taking in the entire view. I try to lock it in. It’s a strange thing. I sit here in the Mololo cottage, scrawling and drawing, with the wind in the blackwood and quince tree out the back. It is also in the chimney, and through the acacia seeds rattling outside and the sea is white horse–whipped and bruising blue. I return my eyes to the table and turn my back to the extraordinary view of Big Dog, just over there, but I want more time. I go, I return, but I’m greedy for it, ridiculously greedy for what it was, for family.

It is all-important to the family, but absolutely, totally, meaningless too. It is just a fleeting bit of place and people who pass, and yet, everything that we are now.

There were a couple of calls from Jo and Charles checking that Bradley was okay. He was only 15.

The quad bike chugs back along the track, through those trees again, through those low branches. We are hurtling around the tussocks and the tussock lumps, and with a good grip of my thighs and bum, I roll along with it, and draw.

Dennis: Yeah, but they worked hard all their bloody lives, yep.

Frances: Yeah, they were a good team actually ’cos I remember when Aunty Heather had gone, Uncle Frank would say, I’ll talk to Heather, or something, and he just … because they must’ve talked things over all the time about the farm and all this sort of thing.

Bradley was there that day for morning tea and he recalled how he and his pop, Frank Willis, would just head up the hill in the car for a half hour of sun. I can feel that wind-free warmth.

Frances: I think that was in the last few years wasn’t it, he liked sitting in the sun and he’d have a bit of a nap.

Dennis: Yeah, quite often you’d go past him in the laneway at the bloody dairy there having a sleep in the sun, yeah.

Frances Henwood and Dennis Gavin, Lady Barron, 2017

Dingo holds a lot of respect for the Willis family. None of them had ever been a problem.

But there were people, maybe tourists, who thought that they could still go to Big Dog, without invitation or permission. They were sooled off, pretty sharply. Dingo wasn’t going to muck around. This is an impressive vision in my mind.

I can feel the loss and empathise with my family, but I wonder how much they really know about the Aboriginal island history, and those real tales of Wybalenna. Does the loss of Big Dog heighten a sense that everything could be lost? Is it vulnerability which encourages less empathy and more indignation?

Some family members quietly tell of Aboriginal ladies who’d buy face powder, hoping to whiten their skin.25 They also spoke of the ‘Snake Pit’. They dropped their voices and reported this sad stuff. I discussed this with Cheryl Wheatley in Whitemark, because she had held an installation exhibition about mutton-birding, right there in the ‘Snake Pit’. There on the wall were Tasmanian Indigenous and non-Indigenous families in photographs, celebrating everybody’s contributions to the culture. My father and mother came to see it, and there was Dad, there with his family, decades ago. Cheryl called it a wonderful room of family gathering, a gathering place. It was and still is the ‘Snake Pit’. These days, though, the words have been owned back, repossessed.

I keep seeing in my mind, all of the photographs of the social and family events. The only place I ever see Aboriginal people really mixing with my family, in the past, is on Big Dog as employees.