What advertising or inducements were offered? How did Sydney know about Puncheon Island?

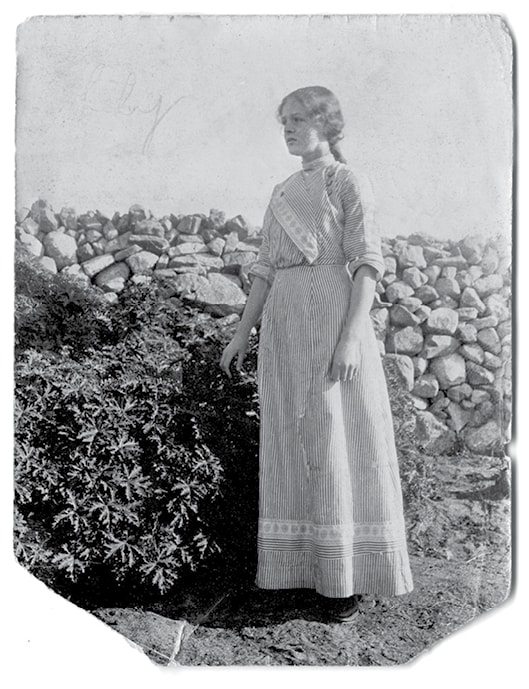

There are very few photographs of them both. In the three or four that we have, they appear quite aged already. There is a later image where Sydney is seated with Ada and Lily, posed reading in dappled sunlight, in cane easy chairs in a yard. A subtle smirk is visible on each soft face, conscious of their photographer but trying to look preoccupied with their pages. The books look the same; perhaps they’re biblical texts. The three of them wear beautiful pale cotton and linen.

Ada and Sydney were first cousins and came from a very wealthy English family. They each had their own money. Some suggest that three previous Smallfield girls had married three Smallfield first cousins. It is understood that our Sydney and Ada were pushed to leave because the possibility of a fourth first-cousin marriage was just too great a scandal. On Flinders, Sydney became a Justice of the Peace and was well regarded and there is some possibility that Ada taught some music. Her small guitar still exists. Nearly everyone holds the opinion that she was dismayed about the degree of Furneaux isolation and would have preferred to stay in England. I think we can be sure that they sailed far away for love.

Judy and Nic Tanner told me that a small guitar of Ada Smallfield’s was most likely made in the 1820s with the machine heads appearing to have been renewed between 1880 and 1920. It is known as the Smallfield Guitar which came out from England with Ada. Carving tools, which belonged to Sydney Smallfield were given to Uncle Bill, and now have been passed on to Bill’s grandson Scott Tanner. Bill was well known for his beautiful carving skills on Flinders, especially for the carving of rose details on furniture.

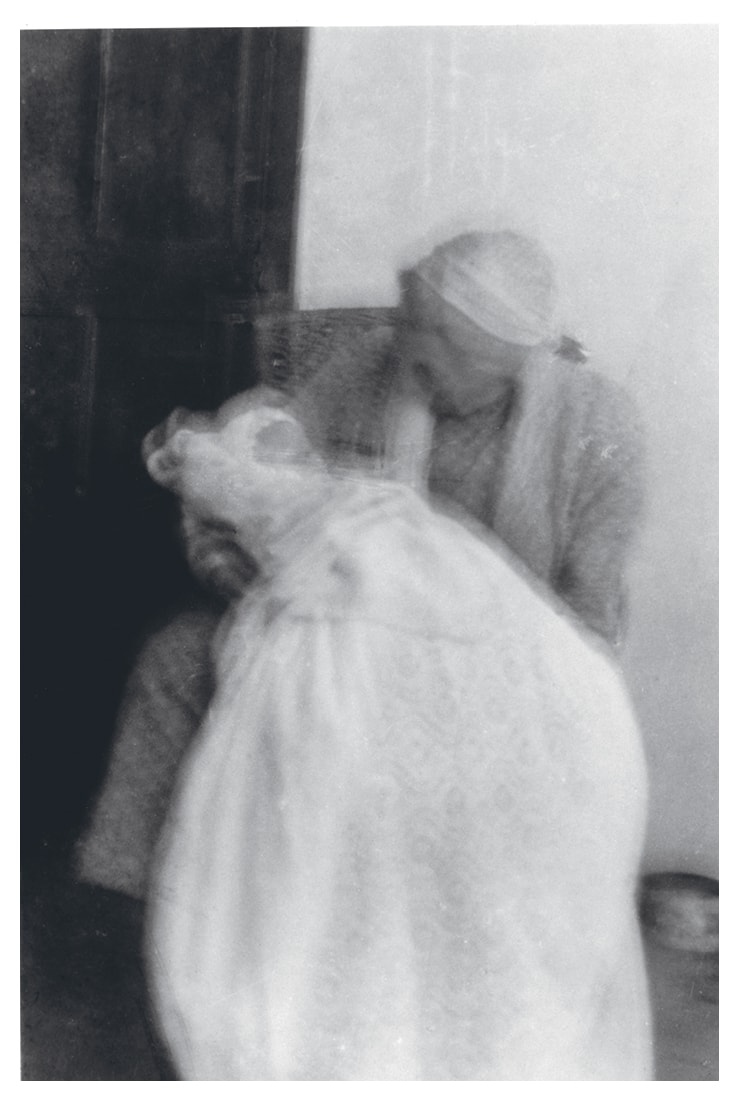

There’s one very blurry image, taken on the porch at Mololo, which appears to me to be a very ancient Ada. She holds a baby, which could be one of Nana Willis’s nine. Ada wears a small bonnet, and in her tiny, bent shoulders I see that it is not long before she will pass. Somewhere here, in our Mololo, she died. When I stand inside, there is nothing of this in the space. There cannot be. It is in my mind, is all.

Inset: Mrs Smallfield, with baby on a christening day, on the porch at Mololo

It is commonly believed that Nana and Pop Willis had no apparent trauma that may have come from this Smallfield couple.

Pop had no family, none that we can find, and the bundle of Mills children, with their mother, Ellen, became part of the Furneaux too.

I look at all those frocks, all that food growing, all that subsistence and that soil development – and that reliance on boats. All that stored food, meat, birds, water and such a camping life, in their finery. There is much to occupy my mind, but so little to build with.

I must take what I can from the images I hold in my hand.

Pop Willis adored Nana. Pop smiles congenially into the lens every time. Even just before his death, his quiet gaze holds the photographer, who surely must have been family. He folds his well-worked hands, composed, beautifully balanced and still. Nana’s square shoulders and stocky hardworking limbs, which were so comforting to my toddler father, are also there, composed, as she too, quietly smiles. This is a rare image of the couple in older age.

Vicki: Yes, well he died at age 60 I think it was. And that was a shock for the family. And after that they all had cholesterol tests. It was after that that Uncle Jeff died while I was overseas in 1976. He played with Lesley and his children and just collapsed on the tennis court at Lady Barron and I was overseas. Mum phoned to tell me. That was a huge shock, so they all had their tests done again. There was a cholesterol problem.

Jane: Pop wasn’t overweight was he, it was just cholesterol?

Vicki: No it was the diet of cream. We always had lovely cream on our porridge, cream with brown sugar, bacon and all the meats came off the farm. You killed your own meats, your own chickens, cattle and sheep. I can’t remember Pop having pigs. I know we had wild pigs on our property, but I don’t think he did. I still remember the dairy up on the hill and it’s a really small hill now when you look at it as an adult. We used to play in the dairy. Mum and her siblings would all have to go and milk the cows before school and after school. They made dresses. Mum always told me that she and Auntie Doreen would be sewing, making their own dresses for dances and things.

Vicki Martin, Lutana, 2017

Here I sit at a dining table, in the cottage of my great-great-grandparents, feeling righteous and full of nostalgia and so comforted in our possession of it.

I float in it, savouring this beloved but shallow pool of ancestry.