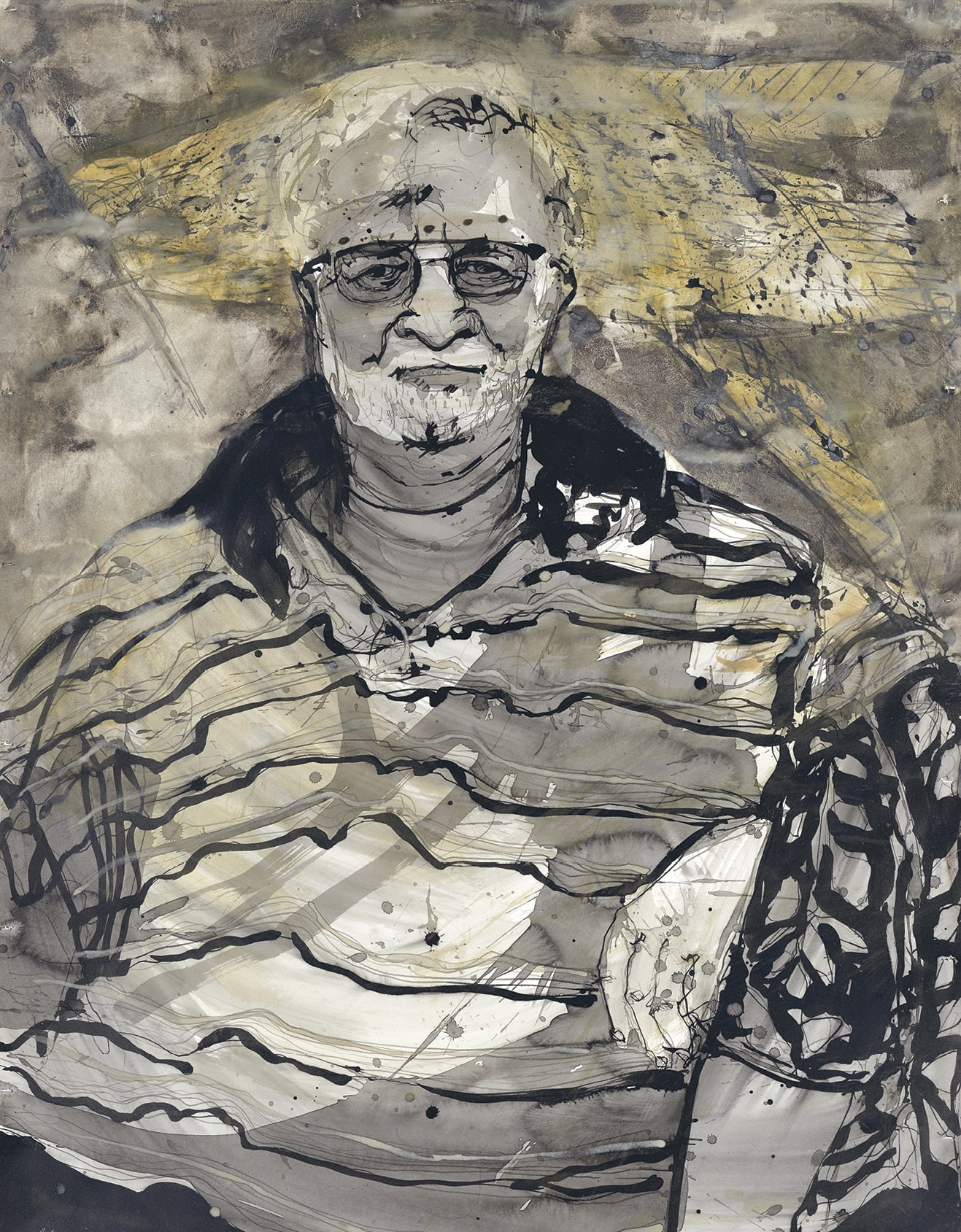

After several attempts to reach an agreeable time, Garry Blundstone phoned me.

‘What are you up to today? Come on then, thought I’d take you up the North East River, if you’d like to see where we used to camp.’

‘I’ll come right there.’

Garry’s words are soft and roll together with his driving as we go up to the North East River. The fields and mountains and outcrops of she-oaks, paperbarks, tea-trees … all bristle and blow.

Clutter, farming gear, living detritus, all around Garry’s seat, just the same as in Tom’s ute, the smell of dirt, sweat and old vinyl, dust, hot dashboard, pens, spark plugs, (rollie filters in Tom’s), pocket knives, faded bits of receipt, an old t-shirt for wiping the windscreen and a spray jacket perhaps, dog hair everywhere in Tom’s. The maleness of these utes; is it the dirt, the dust or the male scent?

The clutter flutters around in the wind and swings all over the place if you’re driving fast … but Garry’s ute is slow. It was very slow, and we reverberated all the way up to the North East River over corrugations so strident over his gentle voice. Garry’s Furneaux lilt is velvet between it all … and so he told me his tales.

Not for an instant did I feel I needed to be anywhere else in the world. It was a simple gift, this one time in my lifetime, with Garry.

He talked the whole way up. The going there was as important as the being there. In the little car park once we were there, we sat in the warm cab, watching those high whipped up horses at the mouth. Oh, those blues were turbulent and that long strip of white extended to an ether far to the south, right in front of us.

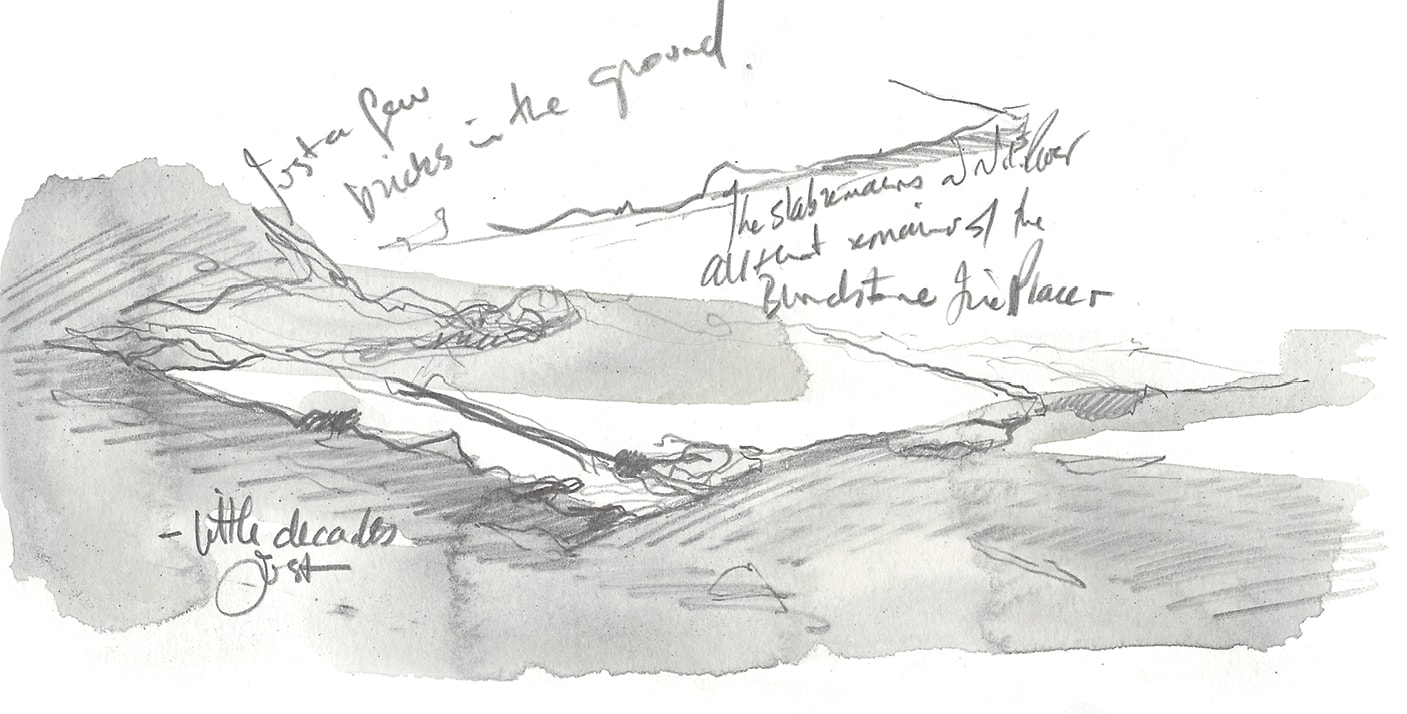

The Blundstones went, every chance they could, to the first camping spot we checked. Then to the second one, which was Barretts’, and he showed me where the foundations were still sitting, merely a flat section of fireplace with crumbly concrete, and bits of brick emerging from now-scrubby earth. He showed me the space where the shed had been, also how the slight clearing of other trees had changed the sensation of everything when you were there.

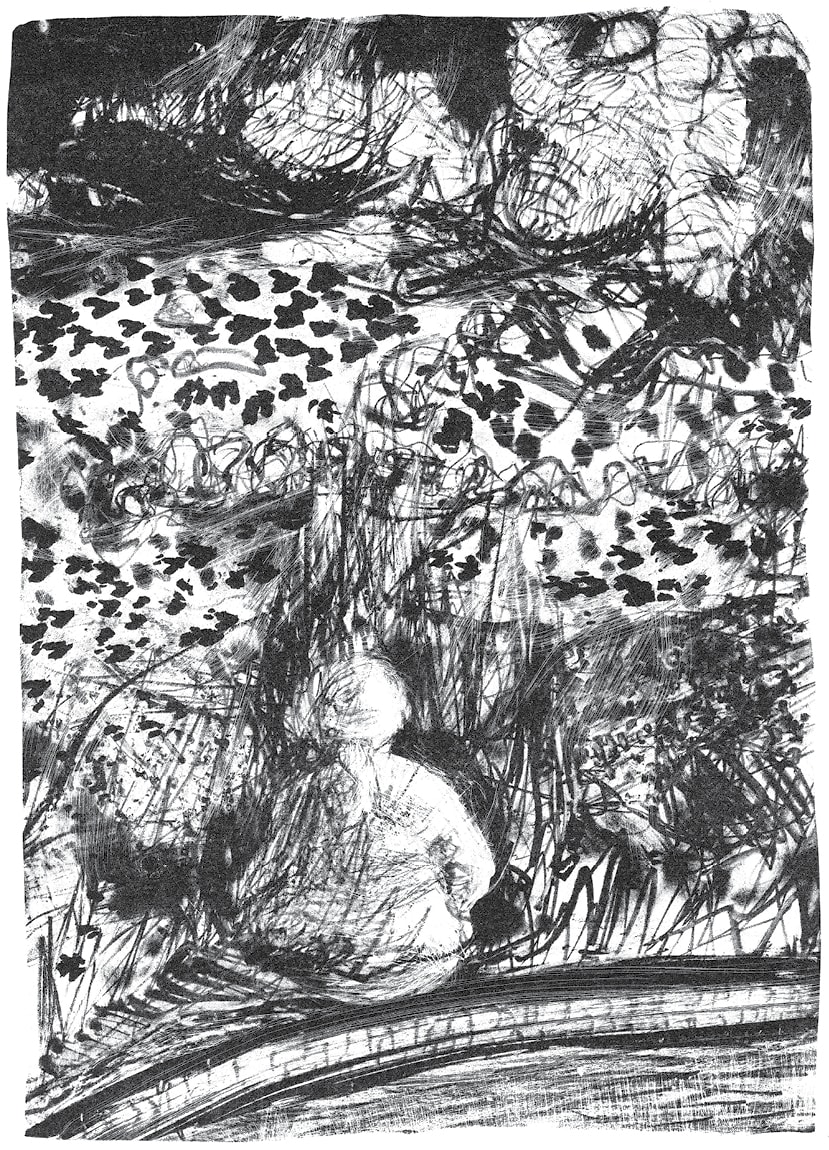

This is where he reckoned the image of Max and the family was taken. I photograph those places where Max had probably stood in his late teens, and then Garry took me along to where his brother Donald’s ashes were spread at that point nearby.

Kelly: Dad [Donald Blundstone] had a shack at the river that’s no longer there sadly. We used to go up when we were little, and you know … you’d sleep with dirt, and yeah, and it’s funny when I go up with the kids now: you’ve just gotta let something go you know, dirt isn’t really gonna hurt them, not so much hurt them, but you know, who cares if they’ve got dirty hands when they pick up a sausage, it’s only dirt! And it’s nothing you never did when you were little. It’s funny isn’t it.

Kelly Blundstone, Whitemark, 2017

Over there beyond Babel Island, near to Flinders is concealed a great space for parking the boat. Garry is happiest when he is nestled in the hull of it, sleeping there in the rolling mass of it in the lea of the islands, listening to the water slapping on the metal sides.

I tell him I will be buried on Flinders.

Garry: Oh yeah, I still want to be on a boat now … I’m half thinking of buying something just to go out to sea and go to sleep out there … I love doing that. If I do get cremated, if I’m away and I get cremated, they’re gonna spread me ashes over Babel, let me go from Cellar Point, that’s beautiful out there. But, uh, other than that if I die here I s’pose I’ll get buried here.

Garry Blundstone, North East River, 2017

He loves it out there. It’s hard work out there fishing. It’s a rough, short sharp swell, tiring. Just being able to go in to moor the boat and sit back and with a good meal and a bit of television is a real treat.

Mick Willis would be with them. In the early days they got the shock of their lives at the size of the swell out there on the west coast. Garry described how on one of those nights there were forty-to-sixty-metre waves and the wind so strong … and they went over the top of one of those waves, swept along in huge sprays. He remembers the boat just dropping, and one of those drops, you know, where everything seems like it is going really slow. It must have been only an instant, but it hit the bottom of the wave with a massive bang. He said he’d never felt afraid. It was too rough to go near the rocks and the little pump was working, with a battery that was kept charged by the motor and he noticed that they were taking on water. But there was only a small risk that they’d sink – as long as the pump kept working it was all going to be okay.

He told the crew that they’d have dinner and then a sleep and after midnight get in the pots.

They’d need time to get some cray … so they all had to wait. After dinner they all settled down, however Garry couldn’t sleep himself, so after a couple of hours he said, okay fellas, let’s get in the pots and get back up to Stanley to off-load. They were perhaps down by the Pieman River area somewhere. So back up the coast, they went.

The pump kept going and all was fine but once the boat was up on the slip, he could see that the huge smack down over that wave had split a weld right open in the boat! There must have been something leaning against it that caused some corrosion, he thought.

He told me that he was more of a fisherman than a farmer. He loved being out on the boat, never felt seasick, just always keen to be out on the water.

Rebecca: Yeah, I totally understand what he’s saying and any chance I got in school holidays when I was little, I’d go on as cook. Pop would organise a crew. I remember the first time I ever went out there, I would’ve been thirteen and it was the roughest trip. The boat would go down into the well, and you looked up and all you saw was water, like it was going to swallow you up. It would come flying up like you were this little cork bobbing around and you couldn’t see any land, cos I remember thinking, when we sink, which way am I gonna swim. Had no idea where we were going. Anyway, and the waves were crashing on the boat and you couldn’t hold the pot on the stove to even boil a cup of tea at breakfast time. I never got ill. I was a bit scared cos I remember looking over at Pop and he was just screaming at one of the deckhands, saying, ‘Pick up the bloody pot you weak bastard, we fished in this weather all the time when I was a boy … rah rah rah’ And I’m thinking, he’s a lunatic, we’re gonna die out here! Anyway, I soon learnt … ’cos when we were little kids we grew up on the boats, we were always on the boat … then when I went for my first real decent fishing trip, we were gone for two weeks, that’s when I realised how hard-core those old fishermen were out in their boats. And their survival and what they lived on. And I really, really loved it. I just loved it. And still every chance I got, I would go scalloping. And I s’pose ’cos I was lucky enough to grow up in the family where I could keep up with the boys and do what the boys could do, so I was always welcome to go as another deckhand, but I’d cook at the same time. So, Dad really enjoyed it when I used to go out scalloping with him because, not only would I be on the deck working with the boys, I would shoot down and make him something nice to eat cos you know, he’d been at the wheel for sixteen hours straight and stuff like that. But it’s just something about the water, the smell and the movement and the feel.

Rebecca Blundstone, Bridport, 2018

Garry: Yes, yes, but I’m not sure if this is up at what we called ‘The Spit’, or where we ended up as a camp … but uh, there’s two places and they’re both … this one goes in, there’s a David Barrett’s (well it’s the Barretts’ now), but, uh, it was … Blundstone Barrett Wing an’, no, Blundstone Barrett Badcock and Wing, no, Blundstone Barrett … Badcock, Blundstone, Barrett and DG Tom Wing too, heading for the river and nothing else to do … Yeah, I’ve got a poem, I’ll give ya copy of it, it’s a great poem, I can’t remember it off by heart, but I can remember Dad making it, he sent it to all these people, in the mail … and they didn’t know where it had come from.

Jane: Well … hold on, hold on, oh my where is it … ‘Badcock, Barrett, Blundstone and DG Tom Wing too, headed for the river, nothing else to do, there they went fishing with the thing they called the net’ and it’s down here … ‘don’t pull ya silly bastard, we’ve got a bloody snag, for I’ll bet that he’s that one that pissed right in my beer.’ I love it. ‘Shall we try one Ray?’

Garry: Well, coming back from Green Island, one of the last trips to Green Island when we were doing the sheep work over here, and oh it was horrible, horrible, Dad’s got the whole sou-wester hat on and he’s on the tiller and the sprays going everywhere and I’m just, can see his lips movin’ and he’s talking to himself, anyway, about a fortnight later this poem, verse comes out, Badcock got one, and Tom Wing got one and David Barrett got one, and Dad got one in the mail, he sent one to himself, and he got ’em all typed out and the letterhead was typed out, so I don’t know who did it, the council, or it might’ve been Olga. But it was somebody who didn’t let on, ’cos if Peter’d wrote it himself, handwriting on the envelopes, they prob’ly would ’a known, and it was all done, and he’s sent one to himself to cover his tracks and his mum and …

Jane: So, you’ve actually got a copy of that?

Garry: Oh yeah. Got a few of them. Mum was … we were sitting there, and Mum said, ‘Oh, I’d love to know who wrote it.’ And I was sat there smiling, and she said, ‘Do you know who wrote it?’ I said, ‘Yeah, I’m pretty sure I do!’ She said, ‘Well, who was it?!’ I said, ‘It’s Dad!’ She said, ‘He wouldn’t of wrote that!’ I said, ‘We were comin’ back from Green Island, he was talking to himself all the way and I’m sure he was reciting poetry.’

Garry: He was making it up as we went along, yeah it was good! David Barrett had it read out at his funeral! But they used to spend a lot of time at the river, Mum and Dad, that was where, every Christmas we’d go there, we used to stay there nearly till mutton-bird season … not there all the time, weekends we’d go up after, we had a tent, we had an old trunk for it to go in actually, on the back of an old truck.

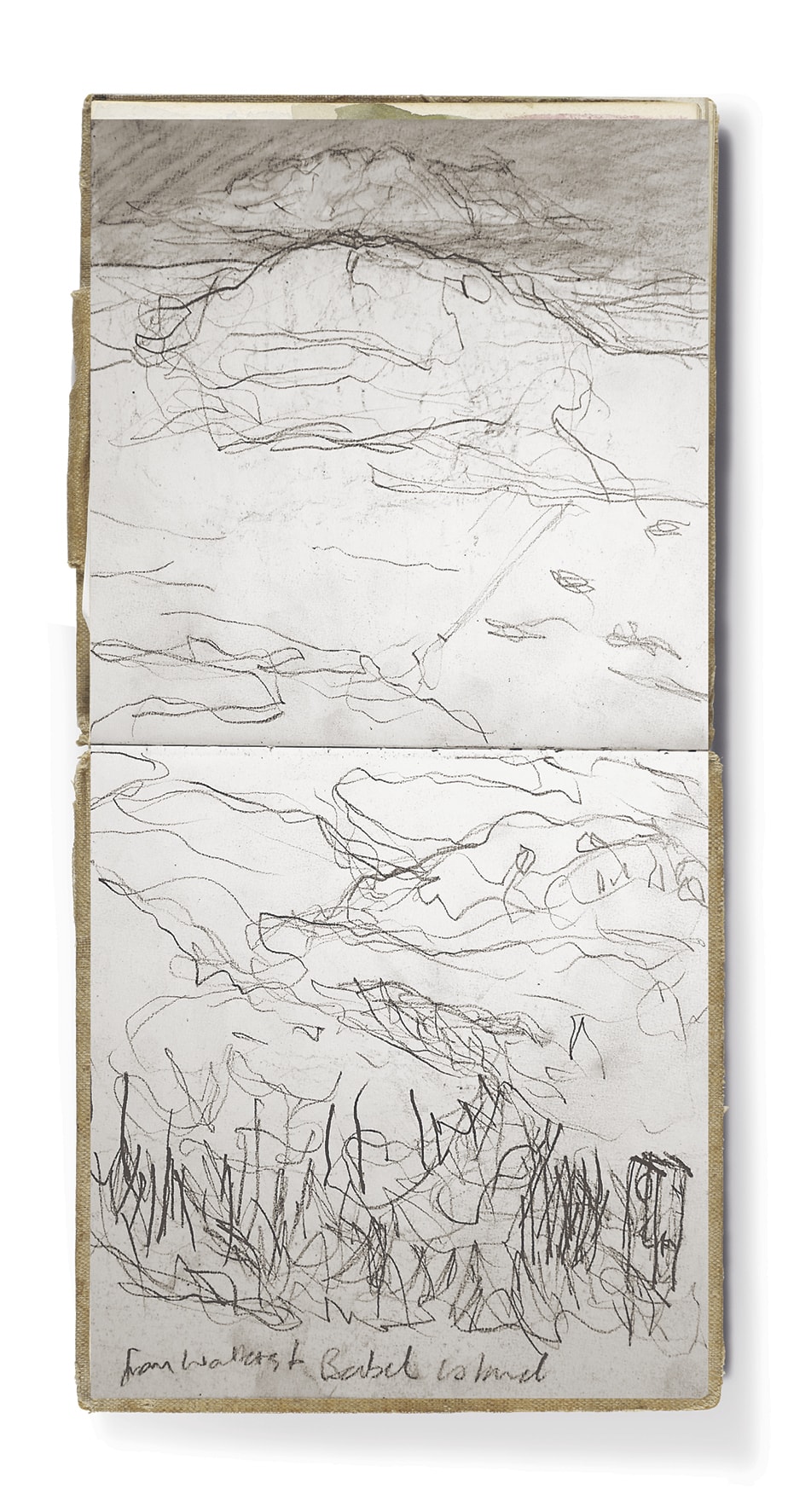

Garry also got what I meant about changing perceptions and distances between islands and water.

He showed me how perception is shifted by viewpoint, ‘Over there, look … you would think that those two islands look like they’re part of the one thing, one bit of land, but they’re not’. He showed me how you can see Babel from the car park and not Inner and Outer Sister Islands but he took me over the other side of the point to show me how you wouldn’t believe that from this part of the north-east point you can see all of these islands, Inner and Outer Sister, as well as Babel. ‘At low tide you can walk across to Babel, and yet from here, see how large the distance looks? Like the big sea, but it’s walkable and you wouldn’t get a boat through there … but heaps of foolish boaters think that you can.’

He said the picture of Garry, Dennis, Vicki, Nigel and Max when they were all little was not taken at Palana but at the camping sites at North East River for sure. This is where they used to go for drag netting. Around the far end of Palana is where they’d go to catch cray, and there was another place, too, but he couldn’t remember now.

Garry: The square one, the kerosene can, that’s what, when I grew up, everybody cooked their crays and things … we went up north with Mum and Dad. If they caught any crays they’d cook ’em in the kerosene can. They had the lids cut out and the handle put in ’em, just like a bucket.

Garry Blundstone, Whitemark, July 2017

On the way back to Whitemark Garry talked about his football days.

His brother Donald was going to be taken in the VFL. He was the best they’d ever seen, better than Darrel Baldock, but he came for one sheep-rounding season to help Ray with the sheep, and having a really good sale, with loads of work and money, he just never went back to football.

He and Sue often drive up the east coast beach and drive around the eastern mouth of the river there. He loves the birdlife, too. We watched the ducks. He was really watching them, in the far distance, taking his time in it all, and enjoying it immensely, the swans, the ibises, oyster catchers, the arctic tern; and the cowrie shells all along the western mouth of the river.

River Happenings

Badcock, Barrett, Blundstone and D.G. “Tom” Wing too

headed for the river

Nothing else to do

There they went fishing

with a thing they call a net

But it rolled from end to end

You can hear them swearing yet.

They cursed the bloke that slung it.

His parents weren’t much class

someone suggested

To jam it up his arse,

The Second haul was better

Things were going fine

When someone gave a mighty pull

And broke the bloody line.

But when the net was landed,

They had quite a few.

One more haul

Another lot like that will do.

Badcock he took over

Blundstone rolled a fag

Don’t pull, you silly bastard

we’ve got a bloody snag.

With the fishing over

Back to camp they went

A belly full of fish and beer

It made them all content.

While around the camp fire

The yarns were being spun

Someone saw a possum

And Wing, he grabbed the gun

I’ll get that little bastard

Pull him into gear

For I’ll bet that he’s the one

that pissed right in my beer.

Badcock the builder

was working out the plan

Barrett the cook

Was warming up the pan

Blundstone it’s reported

Wouldn’t do a thing

While Wingy with the chain saw

Made the ti tree ring.

Everyone is welcome

No-one is turned away

If you have a dozen

And ‘Shall we try one Ray’?

Nigel, Sharon and Roger are siblings who, like their big sister Vicki, speak in short and sharp phrases. They don’t muck around when they wash the dishes. I had not seen the men since I was about ten, so we were all a bit cautious. I recalled wrestling on a backyard lawn with them one Christmas gathering, but only after seeing pictures of them as young fellas. I wonder if they remember.

Description of a Camp Site near a River Mouth

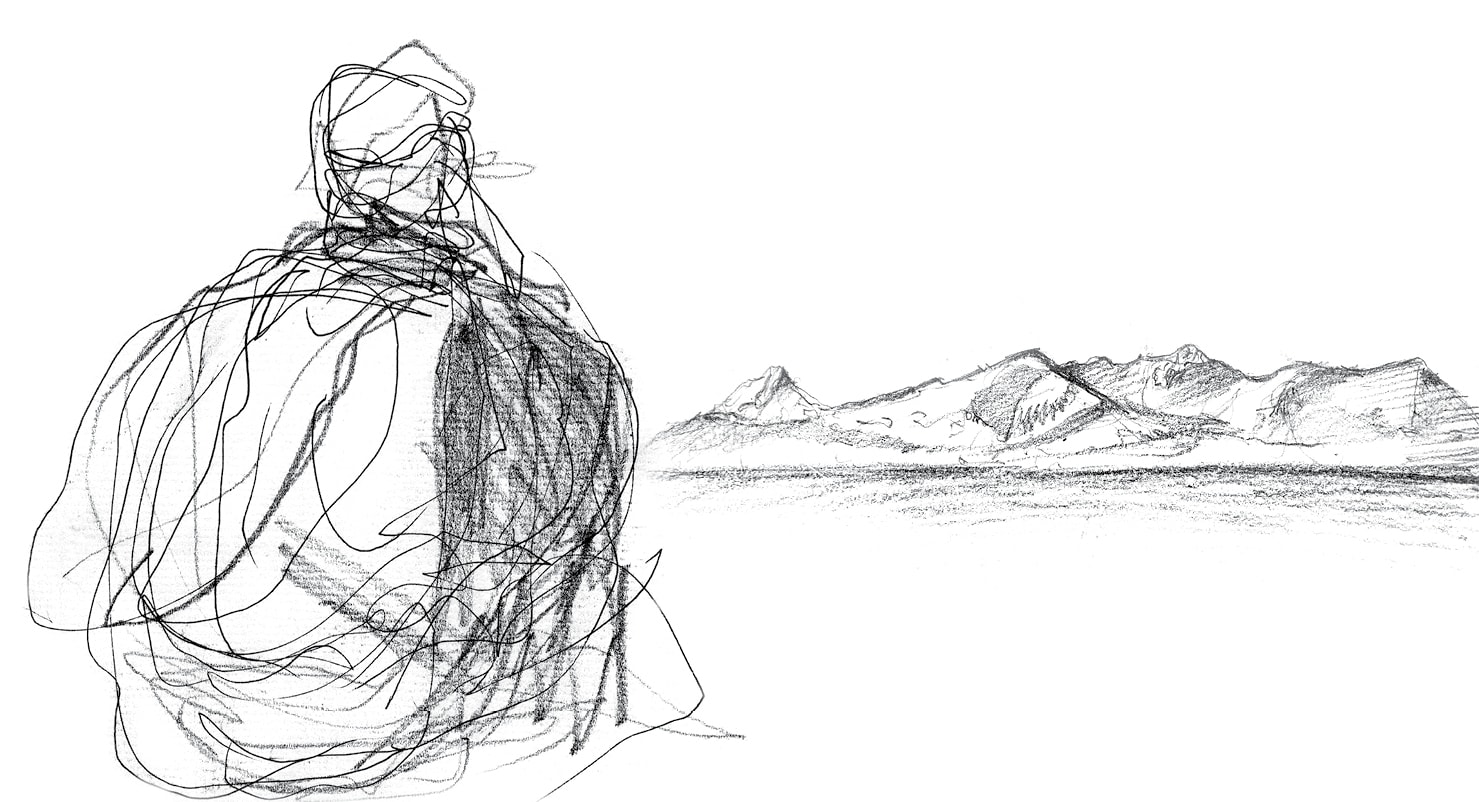

Jane stops at a camp near the river mouth. North points seaward across the spit, upon which oystercatchers are distant flecks. Downriver is a long tidal flat, the soft grey of sand merging into the green of the shallowest of waters. It is impossible to tell whether liquid skims the sand. But there is no doubting the wind. The wind is in and it wants us gone.

We are on an eminence of sorts, and the view is through and over granite boulders as big as a garden shed – bigger. This one is greenish, those beyond more conventionally grey, though the startling orange of lichen provides a sash at the line of high water, and a random coverage elsewhere. Then the beach. But not a beach. A flatland of reed, water, and gravelly sand. There is a white-faced heron, skittish, as they always are. Next, a rock barrier, the purpose and age of which has me stumped. Something to do with trapping fish possibly, though it is not clear how. There are one or two small but invitational beaches. After which the scrub starts.

A little way off Jane is sketching. She wears a beanie, a windproof jacket from Iceland, jeans, has her hair tied back. She looks tough and capable, means business.

She defies the wind. As a child she camped not far from here. A family member’s ashes were sprinkled on the river.

Could be I’m a trespasser. Feels that way.