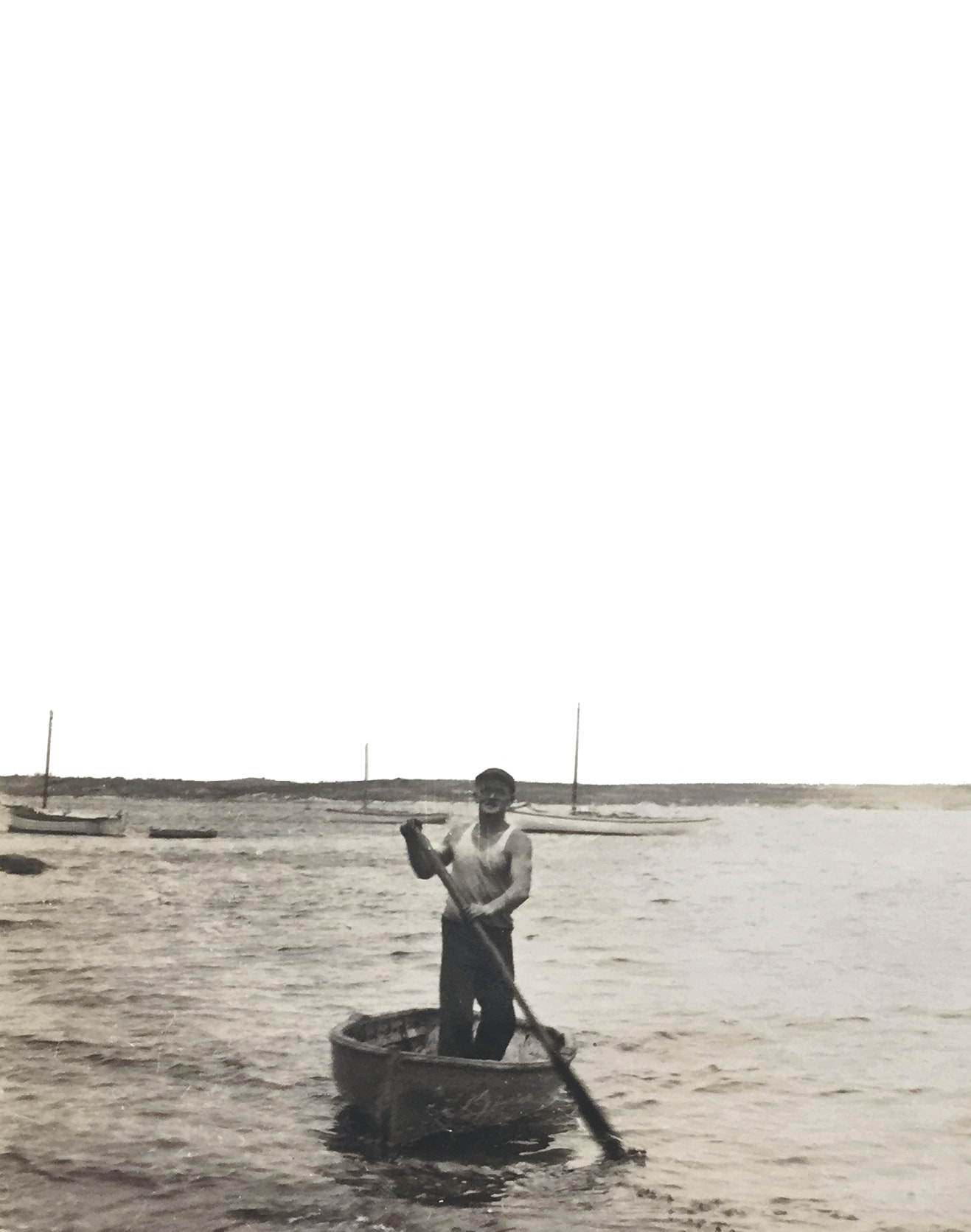

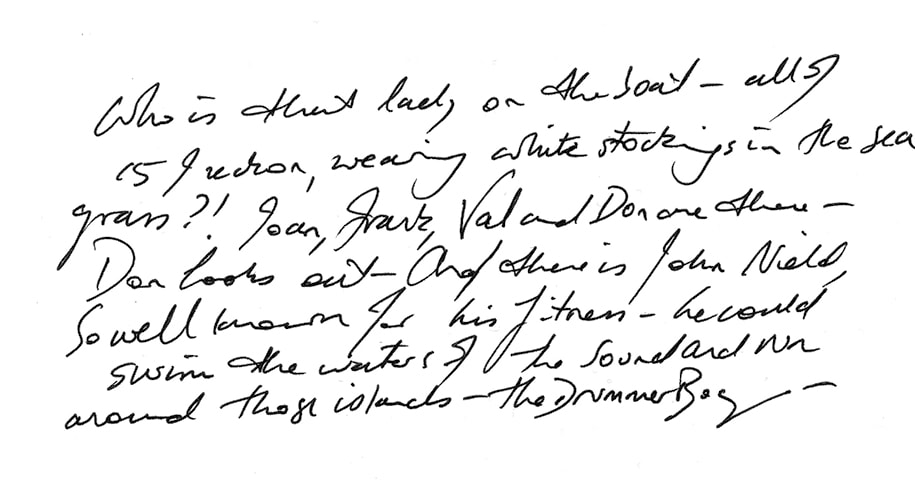

Uncle John Nield swam between the islands. Uncle Bill Mills rowed between them, as did Uncle Frank Willis.

These strapping young men forded the Franklin Sound waters with command, providing for families, the way they had to. They were united with the conduit of their livelihoods.

Bill: Yeah, John Nield used to run around, oh, he worked for Holloways, for old Russell Holloway, when he was just a bit of a lad, and they underpaid him and underfed him, so he used to [laughs] … He told Dad and us and Dory, he said, I wasn’t getting paid much but I was gonna make up for it in food, so he asked for an extra slice of bread, and Phyllis gave him a slice of bread and he put some butter on it, then he reaches over for the jam jar, puts the jam on, she come up with a knife, swipes the jam off, she said, ‘One or the other!’ Either jam or butter. [laughs] Anyway John used to … they didn’t work on the Sunday, he used to go for a run around the whole island … all night beating the drums to keep everyone awake.

Bill Riddle, Badger Corner, 2018

Bruce: Yeah, well John, he was a bloke who used to run all around Big Dog beating his drum.

Jane: Why?!

Bruce: Oh just exercise, he’d run right round it and right round Big Dog. There was tracks then you could walk on. They don’t have tracks like that these days … but uh, he’d made a drum out of a wallaby skin and he had hung it round and tear round and Tom Lowery said, ‘O’course, o’course, o’course! Here comes the Drummer Boy!’ [we called him the Drummer Boy]. Bill Riddle said you’d hear this drum coming from the distance, getting louder and louder and louder and louder and it would fade away into the distance, … [laughs] he was energetic, bloody oath he was!

Bruce Bensemann, Bridport, 2018

Bill: The story goes that many decades ago, some bloke had been getting about the rookery at night with a torch, catching birds. This was – and still is – highly illegal. The police decided to get over to the island and hide beneath in the tussocks just beyond the track edge, hoping to catch this chap. Well, up they sprung and nearly nabbed him, but he belted off at such a pace, they couldn’t catch him! The police ran along after him and down the hill and banged on the door of the first hut they found, waking up a very sleepy shed owner, clearly in his pyjamas and clearly not the night birder. Bruce reckoned, with a broad grin on his face, that the night birder was a very fit bloke. Bruce told me his name, and we all know who he was – a very fit bloke.

Yeah, social family! Used to go to everything, and John Nield, in the start of his courting days … wouldn’t want to go anywhere, so in revenge for the Willis girls 20 going to a dance or something without him, John would run around from Trousers Point, run all around to The Forest (Ranga), climb up the roof and put a bag over the chimney, on the open fireplace, so when they’d come home in the winters and they’d light the fire, they’d get smoked out!

Bill Riddle, Badger Corner, 2018

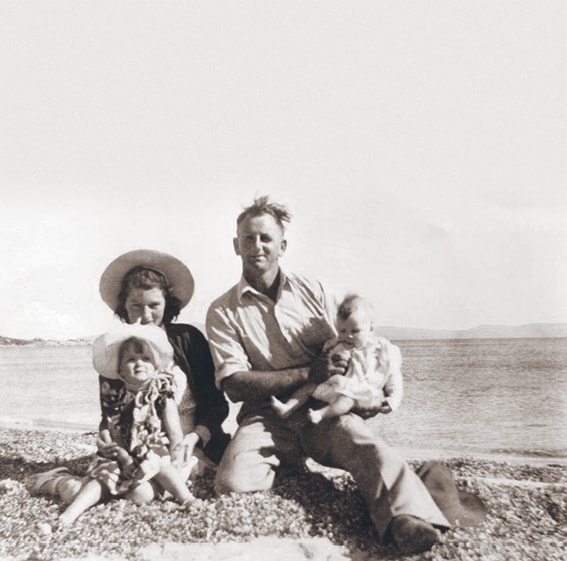

Inset: Unknown, Joan, Nell, Margie perhaps, Frank, Don, Jeff and unknown, Big Dog Island

There are images of children everywhere, loads of images in all our family cupboards and sideboards and on our walls.

Those nine great-aunts and uncles were photographed everywhere and eventually the thirty cousins were recorded everywhere too. People took turns, so the photographs were taken twice, and the poses shifted slightly each time. There are very few that are un-posed, but those that are still possess the moment, the snapshot is ultra-stilled.

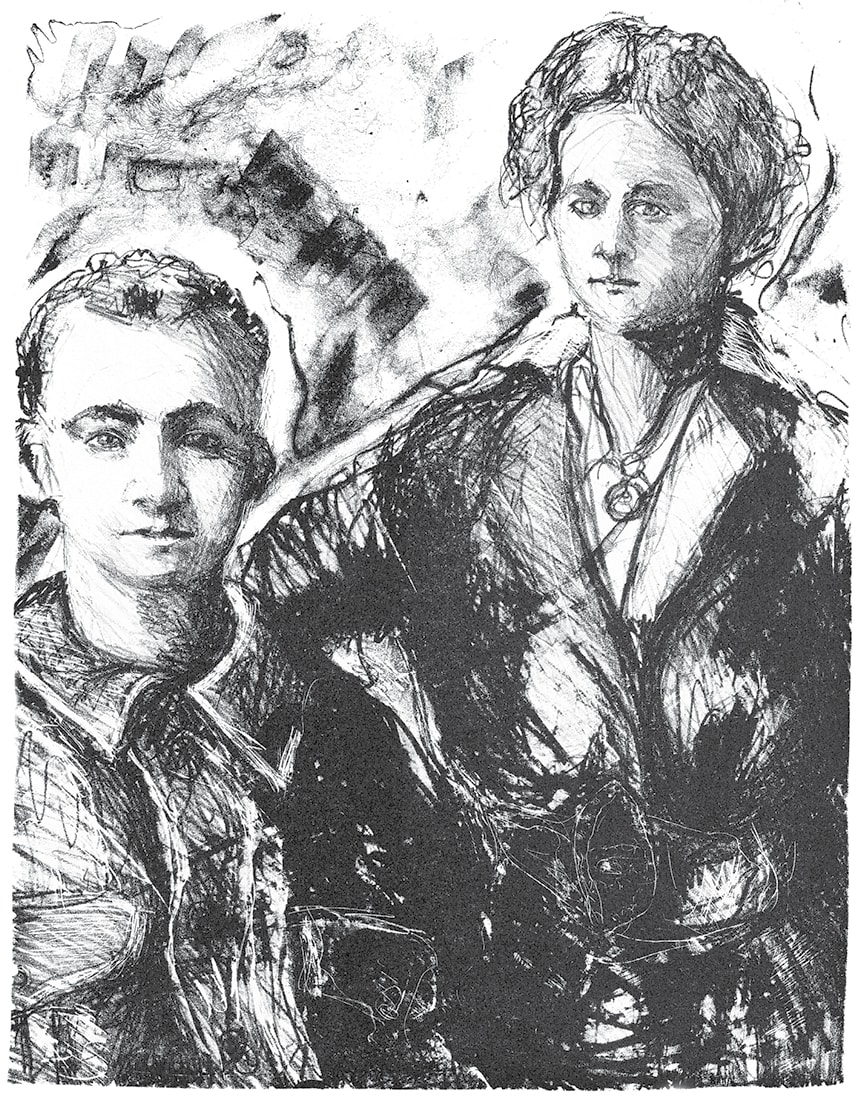

I used Nana Willis’s original Voigtlander to shoot new Furneaux images. Dad gave me her negatives too. Scanning them gave me many delicious moments from images that would normally be considered unprintable by a darkroom technician. Accumulated bits of smudge from long years of handling and neglect were polished off and in scanning these I discovered many previously concealed faces.

Possessing an image of a precious family member, especially from an earlier generation, is rightly prized. Sharing is performed sparingly, judiciously. There are piles of negatives out there and I covet them. I want to gaze into the eyes of those long dead, seeing them from different angles and at different times in the framing by different photographers. They coalesce into gentle revelations of character.

Nigel: In fact, it’s pretty amazing because my father [John Nield] put his hand down a burrow and found a penguin and the penguin nipped him and he said a word beginning with F that I never even thought he knew. So I confronted him about that and he said ‘never swear in front of the children’. My father was definitely a hard worker. He used to hunt. There’s actually a picture of him which we have, mounted on a horse with a shotgun in a holster down the side of the horse and a whip over his shoulder and sort of like a slouch hat. He’d go off hunting for two or three days, hunting duck or fish or whatever. Kangaroo patties were quite common to us as kids. Mainly the legs, minced up. He’d also have a stick of gelignite in his pouch.

Jane: Was that for fish?

Nigel: Yes, well done. You know, if he saw a shoal of mullet or whatever close to shore … he’d throw a stick of gelli out past them and there was a little bit of a kaboom, and he’d pick up the stunned fish. Some of them I think he sold to the butcher. Very entrepreneurial. His father owned land close to Trousers Point, I forget how many acres. They ran a few dairy cattle there. It was on the mountain side of the road. He spent a lot of time climbing Mount Strzelecki or in that area. He said he used to bowl down rocks from the top of it.

Nigel Nield, Lutana, 2017

The images become a greater hint to the truth.

Characters have been merged by memories into socially acceptable forms, cleaned of their very human flaws. Ragamuffin’s face (see Pete Hay’s poem, Ragamuffin, page 145) reveals a wilful stubborn little chap, a naughty opportunistic boy with a quick eye. His mouth is small and determined; it does not pout, it points. In several images I see that he is only just, just doing as he is told. This is also the look I saw on his face as he walked, cigarette about to be lit, down a Melbourne street. He, the soon-to-be vanquished, was sharpish and possibly up to no good. This may be unfair, but it is almost all I have. There are no reports about his behaviour, his character; nothing at all but my few visual residues and suggestions in a loving letter.

The children, the Willis family, are rarely portrayed in any formal way. Even though they’re gathered, they’re always outside, for the light of course, and usually on the grass or the beach, or the seagrass, on rugs … they are the parents and scatterings of children, a tribe, in their ‘will you sit still’ kind of moments.

‘The Willis Family’ is often written somewhere, on the back or front, and as it must have been for so many families having gained their soldier settlement acres, having married and produced their bag of kids, here was evidence of some sort of success, achievement, worthy of recording.

Trish, Ken, Helen, Ray and Anne are my Melbourne five. I chatted to Ken who has the genealogical research drive of the family. I saw him last more than fifty years ago, on the lawns of the Launceston City Park where my parents had rented a semi-detached cottage which is no longer there. While these cousins of my father were raised in Melbourne, they are soaked in the sea and their knowledge is proud. We are all from Flinders Island.

Jane: What’s your earliest islands memory?

Vicki: Right, from a baby I was there.

Jane: When were you born?

Vicki: ’48, on Flinders. We were all born there then. Even Roger in 1960 was born on Flinders Island and Mum wasn’t about to leave until all her children were born there. Then Dad moved us to Launceston in the June. He was a month and a half, barely.

Vicki Martin, Lutana, 2017

In the images they all look tall. This is quite funny, because in fact the Willises are small people generally, and while some of them remained skinny (Nell, Joan, Uncle Bill) most of them were actually quite stocky.

The Mills lot (Nana’s siblings and her mother Ellen Jackson Mills) seemed to be finer boned, though not Nana. Michael Mills, I reckon, must have been a stocky chap. A stocky Irish chap. My great-grandmother was stocky. She looks tough and work-worthy. She was stout of single-breasted chest and belly and had wonderful muscly arms, even in her seventies. Pop died in 1957, and thereafter she slims down. She must have kept working with family – at farming, gardening, cake making, and, of course, mutton-birding.

Birding work was exhausting for all island women. When Joan Blundstone was about 12 her mother had a ‘nervous breakdown’. All eight children were left with their uncle and Joan’s father took his wife to Melbourne for a three-

week holiday staying with relatives. Joan cannot remember her mother behaving strangely … Only years later were they told she had had a ‘breakdown’. Joan believes it is hardly surprising, as she ‘never had a holiday and all those children, very little money and for years she did a mutton-bird season every year’.21

We know that they – Nana and Pop – shared a long and very true and great love.

Frances: Yeah, yeah, they’d have their little sherry and go in and sit on the end of the bed and have a chat together.

Kerry: And out, all the children out. And it was their time. And they had the … demijohn, and that was so dear to Nell that demijohn, because that’s what they used to go get filled up with this, must’ve been sherry, I guess.

Peter: Sherry, yeah. Nell snuck in there one night, just inquisitive, and she said it was one of the most beautiful things. Because there they were on the end of the bed, at the end of the night, kids were all in bed, and they sat down and Pop got the sherry, gave it to Nana, and they sipped. And she said, all I could hear was ahhh, relax.

Kerry: And didn’t he used to take Nana’s shoes off? Pop Willis would just sit her on the end of the bed with a glass of sherry …

Frances: That was a lovely story for Aunty Nell to keep thinking about.

Kerry: So, I love that feeling of their home was a sanctuary and there was to be no aggression or sadness. And you imagine Pop Willis landed on the twenty-fifth of April at Gallipoli, he was in those first boats, and all of that trauma that he would’ve seen … and he gets enteric dysentery and shipped back to Hobart, catches up with Olive and marries her, and then they send him back to the Western Front … And that’s when he gets the gunshot wound and has to come home. And you think, he had two of the fiercest battles and then he comes home and he’s such a gentle soul. And even the few photos that we’ve seen of him, you can see it in his face.

Frances Claybrough, Peter Gavin and Kerry Davenport, Mololo, 2018

Max: He was full on making a living for the family. And that took him away from the family a lot, in the paddocks and out in the bush. My recollection is that he was certainly a gentle grandfather and I didn’t know at the time when I was being looked after by them, that he was always hindered by his war injuries. You can pick it up in the photographs, I think. Probably his right arm, which would be more disabling than his left arm for someone who’s right-handed I think, on a farm. But he managed. I think he used to have hired help there occasionally, there were strangers there from time to time. They just eked out a living on the farm at Ranga for all those years. He was a fairly small stature, I think. I only knew him until the age of 13 or 15. I think Mum might have got a phone call. We heard about the death and she came into the room and she was in tears, and Pop was gone. She went off to the funeral but, so fifteen years is not a long time to get to know a person, even a grandfather.

Judi: You were close to Pop because he raised you until you were four years old and you used to sleep between him and Nana in the bed. I can remember Nana saying to me that you used to run after Pop pulling at his shirt and saying ‘Cakie Poppy, cakie Poppy’ and he’d always go and get Max a rock cake. You would chase after him before you could speak properly. Max had those four years with his grandfather which he was honoured to do because others didn’t get that privilege. That’s why you’ve got a gentleness, well, that’s what I think anyway.

Max and Judi Giblin, Shearwater, 2018

Nana took up with no other man. She certainly socialised and was entertained, but apart from an annual CWA overseas journey, she focused on her living family.

Peter: Oh yeah, and they knew how to enjoy themselves. In 1977 when Mary and I got married, Nana was there and Mum and Dad, cos everyone was having a few drinks you know, but then, I don’t know how the conversation or topic got introduced, but Mum was telling all of these people how she could stand on her hands, do handstands. Well, they said, oh well, show us. Well, after about fifteen minutes, Nana said, ‘Nell that will be enough’. There was Mum doing handstands, her dress had come down! [laughter] … complete strangers!

Jane: So, Nana Willis said ‘That’ll be enough?’

Peter: Nana said, ‘That’ll be enough Nell’.

Kerry: What about when Nell used to wash her feet in the sink, she was well into her eighties.

Jane: What, so she’d lift her leg up and put it in the sink?

Peter: Yeah and put it in the sink and wash her feet.

Frances H: Aunty Nell used to do that.

Kerry: Aunty Joan [too] … we’ve got Nell’s eightieth birthday, you know the night before Nell’s eightieth birthday. We all went down to the pub and Aunty Joan’s got her foot up on the table, just like sitting here, and her foot’s up on the table! And we were all admiring her foot, don’t know why.

Frances Claybrough, Frances Henwood, Peter Gavin and Kerry Davenport, Mololo, 2018

While pregnant with me, my mother was so morning sick and thin that the family sent her over so that Aunty Heather could help her break the cycle.

Fully swept up into the Willis family, she was not used to such a large group and found my father’s clan an intrusion sometimes. In its scale, traditions, expectations and rural gossip, the Willis family would have been a force to be reckoned with.

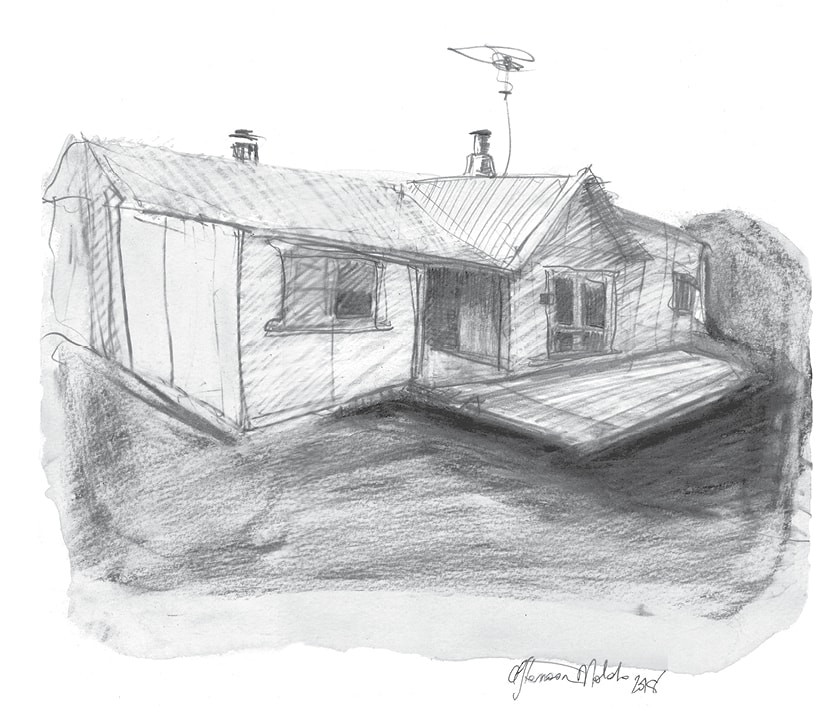

As a young man, Uncle Bill Mills, Nana Willis’s brother, had lived with Ada Smallfield in Mololo after her Sydney died. Ada asked him to move in because she needed assistance or company, and so Ellen moved in too. Ada left Malolo to Uncle Bill in her will. There are blurry images of wonderful ancient ladies on the porch. I wonder if these are Ellen and Ada. I have an image of Bill as a young serious looking fellow, sinewy and watchful, standing in front of Malolo. He looks gnarly, and is flannelette shirted, earthy and warm. I can just recall his voice, and his small kind mouth.

Now that we own Malolo, and title it Mololo, we think of Bill, Ellen and the Smallfields in it.

Bill: Puncheon Island, yes, the Smallfields owned that didn’t they? He had a fancy upbringing, the Smallfields were aristocracy! … Well, they made out they were. People from here, the Robinsons went across there for dinner, they were obliged to stay for dinner, and the Smallfields used to dress for dinner. They wore a suit and everything, and they sat down around the table and they had their little fingerbowls there, old Bernie drank all the finger bowl rosewater, flicked the rose, ha ha, and drank all the water!

Bill Riddle, Badger Corner, 2018

Returned Man

I haven’t the right to place words in the mouth of a man who survived Gallipoli and the Western Front. A man who returned with hair prematurely white.

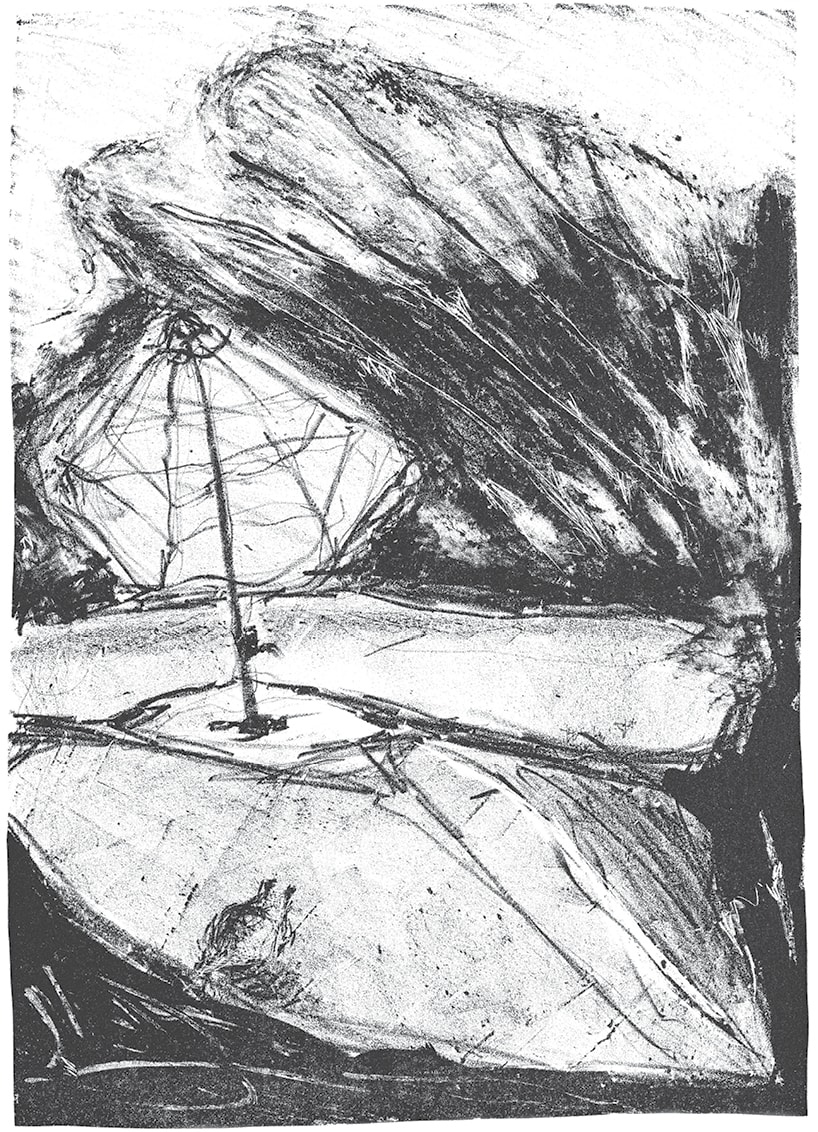

I can, though, imagine him here on Cape Barren Island, gazing north to Puncheon, an achievable swim away, that much smaller island having featured large in his younger days.

He plans a family and this, too, I can imagine, for this is the lot of most men married new, and of like age. It is a matter of forming a future from the wreckage of the years of mud and stench and flying metal, the years when death waited at his shoulder.

His shoulder, yes, the shoulder that took a bullet. It would throb as he sits here, it would have to throb, there where the bullet crashed into bone and muscle. I wonder whether – I wonder how much, rather – it constrains his life. He is birding now, or soon will be. Is he a one-armed birder?

And always the trenches. How does he bring the trenches into his present? Surely he must live, one way or other, with the emotional baggage of those years of slaughter. With the memory of dismembered bits of men he has known. With the scream of incoming bombardry.

Putrefaction. The hell of no-man’s-land.

All this is his, and it is not for me to reconstruct his

minding of it. Life is ahead of him. Love for the bed-sitting woman whose shoes he reverently removes each night. The laughter of children. A shed on Big Dog.

He gazes over still waters to Puncheon Island. May his mind be as still. I leave him to resolve the blasted,

entrenched past. To make calm the waiting future.

Lady Barron: A Sonnet

Here is Franklin Sound, its water purest aqua, colouring the morning light and lovely; sky, town, shore.

Wharfboys idle over whether to fish.

Penned and frantic poddies, bound for some killing floor, provide a forlorn aural counterpoint.

Below the brash murals of the store codgers work up a yarn, spilling geriatric glee.

This is Lady Barron in the hours of light, a peopled realm, its hours shaping the mystery of a town’s private, scurrying ways.

Comes dark. Folk retreat to curtained dens, cede primal space to possum, pademelon, red-necked wallaby.

It is their town now. Though placidly known, the portent is hidden:

that place here is unconquered, and while it persists, will ever be.