My dad used to go spearfishing for flounder at Badger Corner. When I was really little, I was fascinated with his spear and torch.

The spear rod was enamel green. Perhaps it was red, and the torch was green. I don’t know. I found them enticing for their use, but also for their visual structure. They were linear and hard and felt well weighted in my hands. Perhaps it was just the torch: green enamel paint, metal and set at a particular angle so that a flat arm under water could comfortably light the sandy bottom.

He tells me that he only floundered once when I was little. It would have been at Port Sorell where, at four, I was allowed to eat my first lolly. He says that he’d have taken the torch, with its battery in his pocket but its strap over his shoulder, and that the torch had some Vaseline around the seal as protection from the water. Yes, he tells me, yes, he had a spear, and yes, we think it was red. The torch memories I have are correct except there is no lip, just white enamel inside and an angle in the enamel to reflect the light.

He said I would have seen him go out just that one time. In every tool shed we ever had I saw those spearfishing tools against a wall, in a corner there, and I knew their little history.

Dad was young when he floundered at Badger Corner, so he went with family. The activity in a place is the relationship that makes it meaningful to him, to me, to us all. I look at Badger Corner these days, and it is like every little rocky beach around Tasmania, but Dad points it out as a place often enough, and, thus, it is sewn into my self.

I watch, on social media, the members of my dad’s generation wander away in an array of camping vehicles. They find a spot of dirt by a river, near some straggly old gums, or a patch of grass near a beach, to join others. They barbecue their dinner and sit in foldout chairs, to drink and play cards into the night.

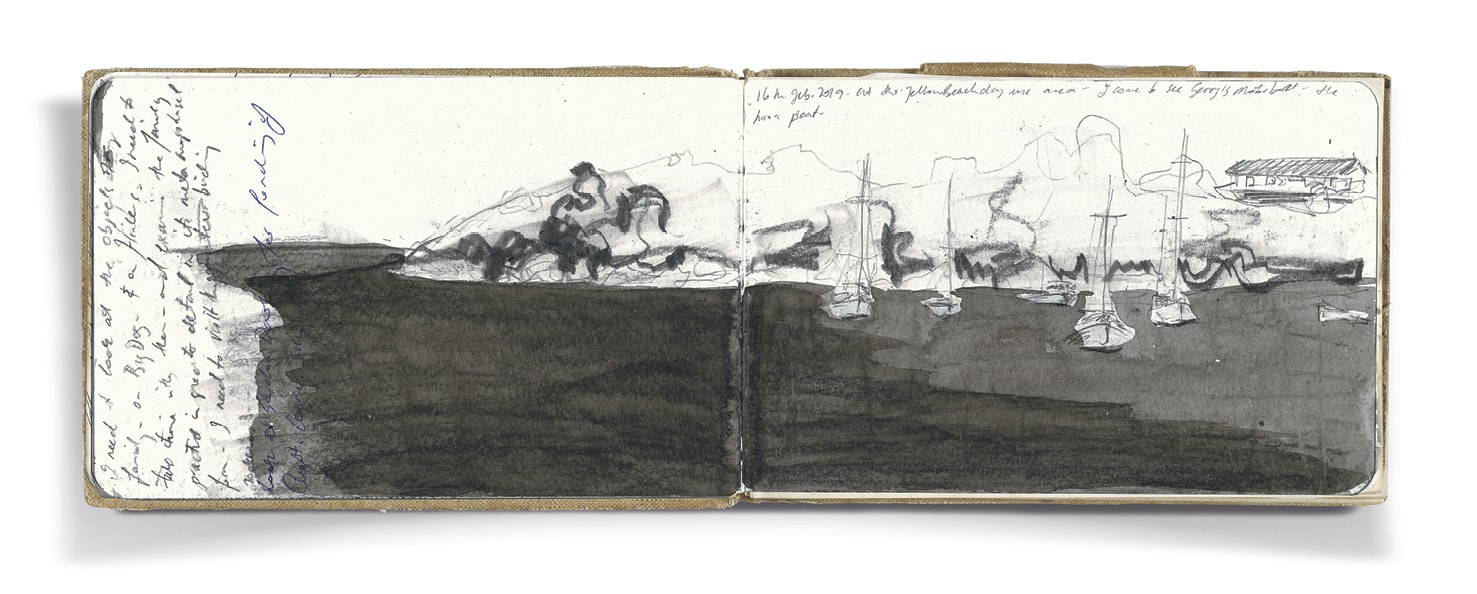

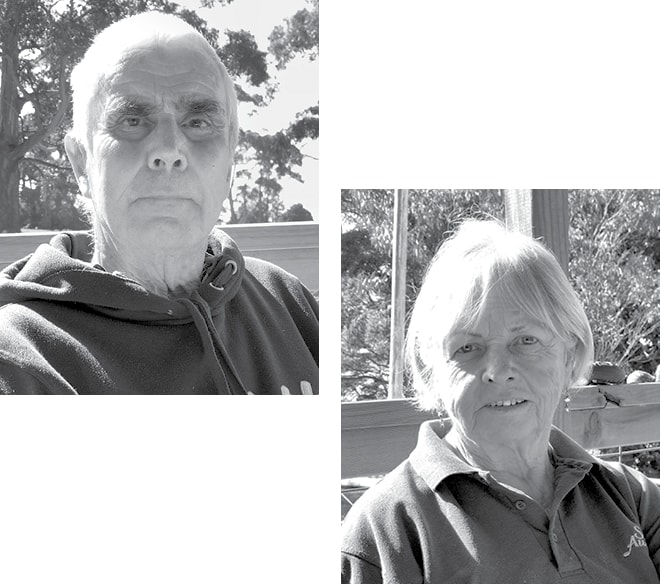

live in a wonderful sprawling home with a verandah that looks out over Franklin Sound. The Riddles were friends of my great-grandparents and great-aunts and uncles. Bill is a statuesque octogenarian. He and Maureen gave Pete Hay and me a beautiful morning tea on their sunny verandah while their terrier, under the table, contentedly chewed away at my handbag strap.

Pete: When you say that you couldn’t live away from the sea, does it have to be the sea here, could you live on by the sea on the Queensland coast for example?

Bill: I think just the coast and the surf and the moon and tides, it’s always changing ya know, you look at this here, you can see the reflection, not a flat colour, and tomorrow it could be a storm … whirlwinds going out, just beautiful but everchanging. And I think some of the most restful times of my life were spent on Big Dog. We were there twenty yards away from high water mark, and you’d go to bed bone tired after the mutton-birding, and you’d hear the wash of the waves on the beach, swish, swish … just puts you straight to sleep, yeah, relaxes. I think anyone that hasn’t witnessed that has missed out on something, in life.

Maureen: … My dad was born in England in Devon and um, they were near the sea, and he came out to Australia at fifteen and went straight to the middle of New South Wales to a place called Ganmain and learnt farming and what have you. And so, all he wanted was to be back near the sea but able to be on a farm, you know, have land and that around him, and of course when Uncle Jim came here, and they came down and saw it, they fell in love straight away with Flinders. So eventually we had West End, so. So that’s in my blood also, to just be near the sea and land, and have the land around us.

Pete Hay, and Bill and Maureen Riddle, Badger Corner, 2018

Inset: Willis Family and friends, including Don, Frank and Jeff and Molly, Ellen Mills and Pop Willis

Samphire River

We slip through a scarf of paperbark to the river. We leave behind farmland, enter another world, another living assemblage, the one that was here before we who make over the land arrived. It is a sorrowfully small ribbon of the old, but it is complete. I am enchanted.

Dusk is upon us. The river is the realm of birds, songful, busy in the urgency of their preliminaries to sleep. It is their world, and I am glad for them.

All scorn, river-backed,

where the water strokes the mud,

gorged, a great egret.

The egret colours the river. Punctuates it. But the inked colours of dusk reach for it, stalk it, its only predator in the still, looming night. It is the river’s descriptor, and so, for me, will it ever be. The night will claim it, but only to a point, for the purity of such white is inextinguishable, and will prevail.

I look to Franklin Sound, a mere hundred metre paddle away. And, were I of a mind, paddle it I could. There is a boat here, right here, at the only mooring on the river, and that is why we are here, we three, though I am the interloper. The boat has a long family history, and much of its history is known. Built in 1938 by Lanky Virieux from Huon pine offcuts in a Launceston shipyard, it has been in the same family since 1962.

For 10 months of the year it has lain dormant, for its sole use was in the birding season. It may have been built as a rowing boat, though it is big and heavy and has been diesel-powered since it came into the possession of this one family. The river mouth has a single foot clearance, and the boat draws two, so getting over the bar involves a

pronounced scrape…

Who does not love an old boat?

Who is not touched by the mystery of it?

The map of time that it sketches?

The comfort of it at rest,

The way it complements a mooring, lends it its own dignity…

I am moved to photograph the boat’s prominent bowpost. It is proud and strong, fit to safely lead the boat wherever it might take us (it configures the prow of a Viking longboat). And there are other photos, these from a lapse of time – here the boat has been tricked out in white, lovingly, and holds a season’s gear. It is loaded for Big Dog with a collective care. It is the season, and this is its time.

At the Samphire River the black drape of dusk draws in from the west. The remains of the daylit river are spangled by the low sun. These are the last minutes of the day, the last minutes of a riverine beauty without compare. One last soul-soaking look. We leave.

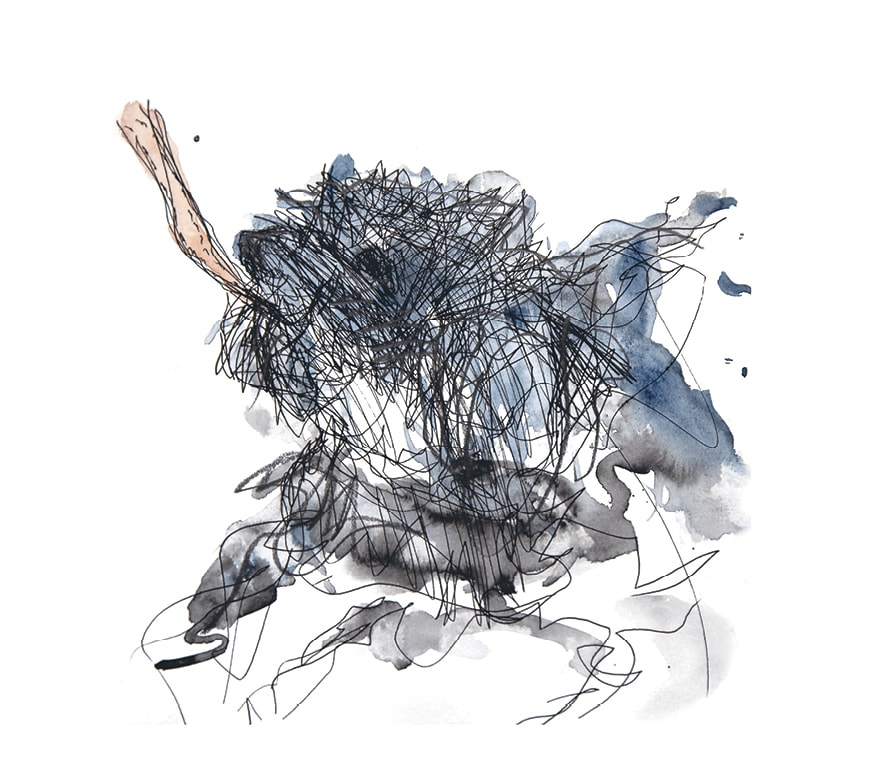

Swimming Nude at Badger Corner

People lived around here then, and there are reputations to mind. I imagine fingers

locking, and eyes, the eyes alive with daring, this all in the eyes, not spoken. It’s settled, the eyes have settled it, and there’s no recanting now. Can you be brazen and furtive at the same time? Scan the road, scan the farmhouse over the way, prime the ears for human presence. Frarrrk. That’s a raven. Tch-tch-tch. That’s a wren telling other wrens there are humans about. Humans soon to be divested of clothes. The affirming hands lock again. Daring eyes. A grin, returned and conspiratorial. Who starts? Not important.

Off come the clothes, cumbersome even in autumn. There are snags and stumbles. These irritate, and they work up anxiety. But there it is. The naked, beautiful, familiar body, and it must be admired, perilous though this is. Fingers locked. Faces radiant, triumphant. Delicious wickedness. Turn and face the water. As at a signal – run! Squeal, yell – though this is dangerous. Plough the water.

It is safe now. Nothing to be seen but two bobbing heads. Hair clinging to ears and temples, water-streaming, and the smiles are huge. We are people of a different cut. We leave the timid, conventional life behind. Reputations be damned. We will live excessively, invite prim whispers. Fingers locked, we emerge from the water, walk slowly to the bank. A car comes along Badger Corner Road, the driver staring astonishment. We couldn’t care less.