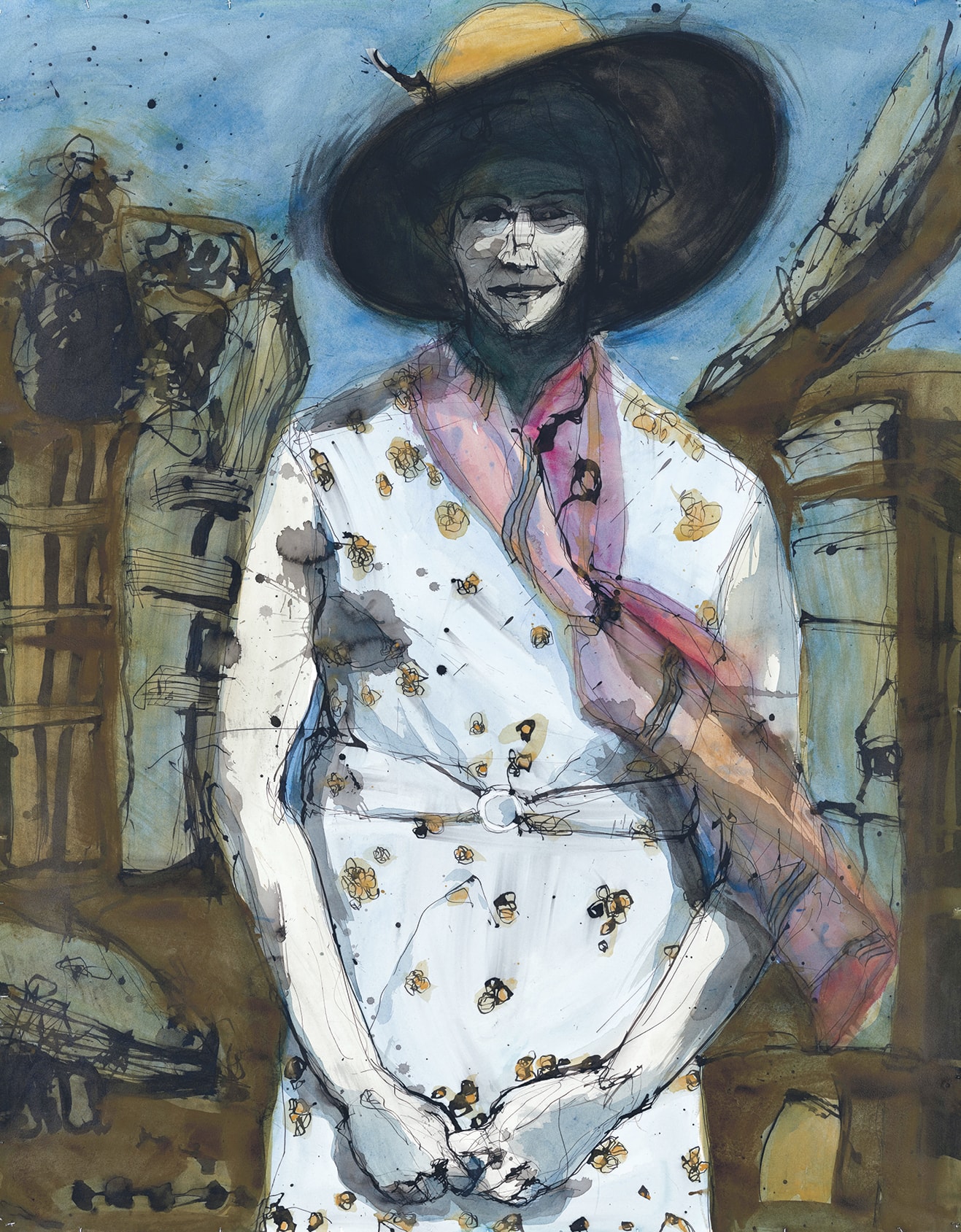

is the daughter of Garry and Sue Blundstone. She is highly regarded as an experienced birder and one of the very few women who bird. Rebecca is alive in the birding, on the sea and in the islands, but lives at Bridport, and still part of the Furneaux in one sense. She is my generation and has a fabulous clutch of children who know, like mine and many of our generation, that they hale from the Furneaux.

Finished work, thought it was an amazing idea. We’re all perched up on the rock. We’d forgotten the birds were coming in at dark! And they were hitting us!

Rebecca: Yeah, it’s of a night, I like [it] of a night as well, it’s just on dark and you’ve finished for the day and you’ve usually had a big day and you’re sitting around waiting for tea to finish cooking itself by the campfire, and you have a couple of beers, and the birds start swooping around. Like there’s some real nice feeling watching them. The kids name them all! I don’t know how many Margarets we’ve had!

Jayna: One year, we kept having birds that’d come down and look for their mum and we’d take one and call it Margaret. And we’d make a little burrow for it – but it would just be like a container or something covered with dirt – and stick it in there. It’d wander off and we’d get it and stick it back in there. Yeah, and just kept calling them Margaret. Don’t know why the names never change. Mm, and you’d see the water rats coming up out of the water just on dusk, ’cos they’d come up and take the birds that are close to the water.

Rebecca: Just all those little things and knowing that, right, it’s a calm day, we need to get these nets in the water and pull them tonight, ’cos the wind’s gonna pick up and we’ve got some fish for tea. Just all those sorts of things. The kids don’t get those experiences when you’re an amateur birder because you’re at home, you just pack up, go in the boat and come back again. Because when you’re living there with the birds, listening to them, oh, they’re so loud when their mothers come in of a night, talking to each other and scurrying through their little tracks of their landing.

We went over to this side of the island, here, there’s a big rock there, and it was years ago when Three Peaks Race was on, and it’s like a real small [birding] crew, got a bottle wine, and I thought, oh let’s go over and watch the yachts come in. Finished work, thought it was an amazing idea. We’re all perched up on the rock. We’d forgotten the birds were coming in at dark! And they were hitting us! [laughs] And we’re all trying to scurry off the rock! But yeah, that was a real funny night you know, we’ve been on that island for years and years and years, and just completely forgot that we were gonna get bombarded and that the rock we were sitting on was obviously one of their landing rocks on that side of the island so … they were swooping around left, right and centre of us! While we were trying to gather all our cheese and biscuits and wine and glasses and take off again. Yeah, but they’re an amazing animal.

Rebecca and Jayna Blundstone, Bridport, 2018

where the Smallfields lived, from the air, with Nana’s Voigtlander camera, 2018

Rebecca Blundstone lives with her husband and children in Bridport, Tasmania and is a member of my generation.

Her father, Garry Blundstone, is my father’s cousin, her grandmother Joan Blundstone is my great-aunt and her great-grandmother, Olive Willis, is my great-grandmother too. Rebecca and her forebears were raised in the Furneaux Islands. She, like them, has been involved in the mutton-birding industry for most of her life.

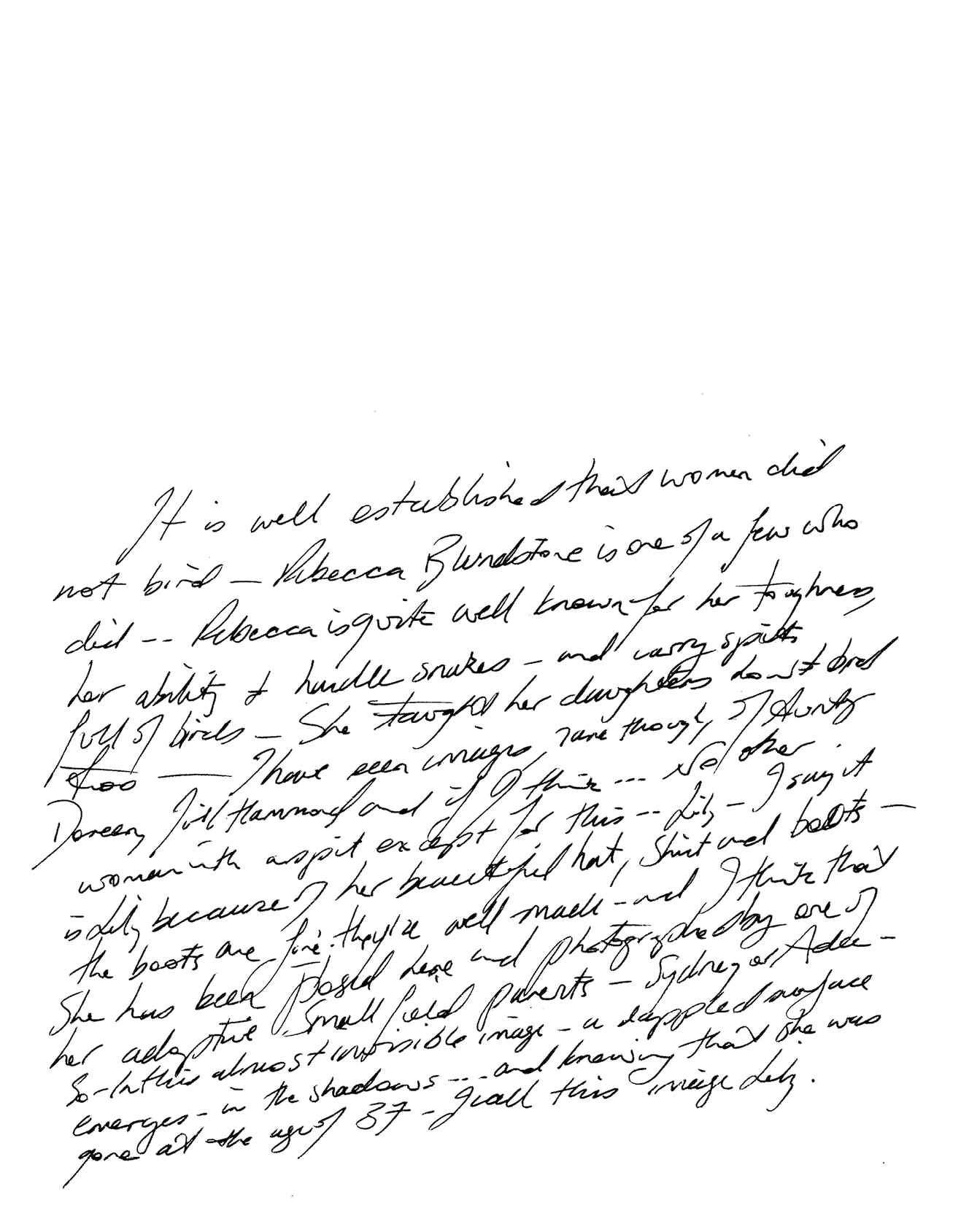

My father, Max Giblin, was born in Whitemark, a small town on the lower west coast of Flinders Island, in February 1942. When Dad was only three months old, his father, Bob Giblin, on his way from Melbourne to visit his new son, died in a plane crash off that Flinders west coast. Bob was a soldier, a minder of Italian interns in Victoria during the Second World War. He is buried in the Whitemark cemetery, on a beautiful windy bank which looks out over a vast and glistening bay. The armed services’ white marble headstone is grainy now, weathering softly, the only one of its type on that bank.

Leedham: Was that the crash that my dad got the bodies off the plane up at …?

Judy: 1942, twenty-ninth May.

Leedham: Yeah, well I remember afterwards they got the aeroplane off the beach, mangled up mess, and us kids were so big … ’cos I remember it was on the wharf at Whitemark, being ready to get shipped out on the Lowatta, this wreck and I thought we heard the story, oh say, from Dad or from somewhere, ’cos Dad was the undertaker, and he got five bodies off the plane.

live in Whitemark in a long low cool house and during my interview we sat at a long slab of marble, their table, which had once been a shop bench. Leedham is a character indeed. He and Judy have run Walker’s Supermarket in Whitemark, it seems like forever, but his father ran it too once. His father worked with Frank Willis up at Palana. Judy is utterly active throughout the community and is a stalwart of the Furneaux Museum. Their son Gerard drives the school bus now.

This was all mysterious, out there, on an island, enticingly close to Tasmania.

My father is very fond of his island memories, and images of the place and his ancestors appeared on walls in our homes and in the stories he shared. As a boy, he was often in the care of his maternal grandparents, my great-grandparents, Olive and Valentine Willis who, while born elsewhere, grew up and became parents in the Furneaux Islands.

Leedham: That’s right, and [they] were really, really, really loving, everybody says they were just the most wonderful couple and that he was known for his quietness and for being a really gentle fellow.

Leedham and Judy Walker, Whitemark, 2017

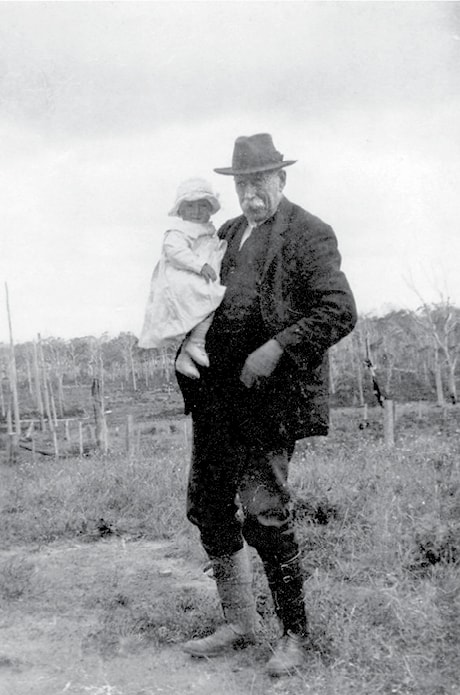

My grandmother Molly had a fabulous chest, a stern bottom and a get-on-with-it step to her stride.

My great-aunty Joan enjoyed dressing sharpish and remained fit and strong for her busy 98 years.

My great-aunty Joan enjoyed dressing sharpish and remained fit and strong for her busy 98 years.

Max is a hale and hearty gardener who has supplied our family with beautifully healthy and diverse vegetables for my entire life.

We proudly count the number of different veggies on the plate. Over the last few years he has had two tiny strokes, which have caused minor damage to his wonderful signature. Since my early childhood, I have watched his pen line follow a large, soft, sweeping form, like the lines of the drawings he made for me fifty years ago. These days it runs with a degree of caution, it falters.

Max’s aunt, my great-aunty Joan, who died at 98, was the last member of her generation and the second eldest of the Willis nine, Olive and Valentine’s children.

Max’s generation ranges between the ages of 82 and 47 and there were thirty of them. Their stories, which originate in the last decades of the nineteenth century, in Franklin Sound between the Cape Barren and Flinders Islands, deserve gathering.

This is not a history tale, but it includes histories. The varying relationships with the waterways and islands of the Furneaux have provided a visual, historical, racial and geographical meander around my family and their Furneaux Islands lives.

The family was instrumental in the primary development of a commercial mutton-bird industry, which resulted from knowledge gleaned historically from Tasmanian Aboriginal people and extended by their own experience. The commercial ownership of this industry has changed and my family is now learning to accommodate a new way of birding. For some, this has not been an easy change; they bristle, as they adjust to the restitution of island lands, once used by my family, to the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania.

We’ve eaten mutton-bird for many decades in my family, bought through family on Flinders. My children were raised on it.

Though I am not an Indigenous woman, I have Indigenous relatives. My relationship with the Furneaux Islands is strengthened by the work of my non-Indigenous and also, my Indigenous family.

My love for the islands is underpinned by solemn gratitude for the knowledge and work of my family. It is also grounded by the knowledge which was handed on by Indigenous women to the Straitsmen in the nineteenth century.

The mutton-bird, or short-tailed shearwater (Puffinus tenuirostris), inhabits the north-east coast of Siberia between June and August, flying south in October to Bass Strait and to the north, east and west coasts of Van Diemen’s Land, but most particularly to the Furneaux Group.

Here, the mutton-birds develop their burrow-like nests in the rookeries at the edge of the sea. During the first week of November they leave the burrows and between 20 and 27 November to lay their eggs, which hatch the following February. The parent birds remain for eight to ten weeks rearing their young and then depart for the long journey to Siberia. The young birds follow in the first week of May. In the early nineteenth century the mutton-bird population reached several hundred million and to the Aborigines it seemed an inexhaustible supply of seasonal food. They would gather at the rookeries along the north coast of Van Diemen’s Land in early December to gather mutton-bird eggs and then again in April to harvest young birds. Mutton-birding was probably more integral to Aboriginal society than sealing, was seasonally more reliable and was exploited by all ages and both sexes. So when the Straitsmen in the eastern Strait seized upon the economic advantages of mutton-birding, they incorporated a most important aspect of Aboriginal society into their own.2

I have a skin, and it comes from this Furneaux place. It is a place where once my extended family did not belong. Over time we developed a home, a community and a great love for the place and the traditions we built there.

Whenever we’re away from it, we yearn for it.

Not long after a conviction for larceny in 1905,3 11-year-old Valentine Willis was fostered out to Sydney and Ada Smallfield on Puncheon Island off the north-east tip of Cape Barren Island, in the Furneaux Group in Bass Strait.

At around the same period, Ellen Mills (née Jackson) lived with her family at 245 Argyle St, Hobart.4 Ellen, however, discovered that her husband, Michael Mills, was keeping a second family.5 In July 1917, a Mrs Emily Glendinning took her to court for trespass; Ellen swooned while giving evidence and the case was adjourned. According to family lore, when Emily Glendinning’s husband died in 1916, Michael abandoned his family and moved up into Paternoster Row with her – certainly the electoral roll shows them living together by 1919.

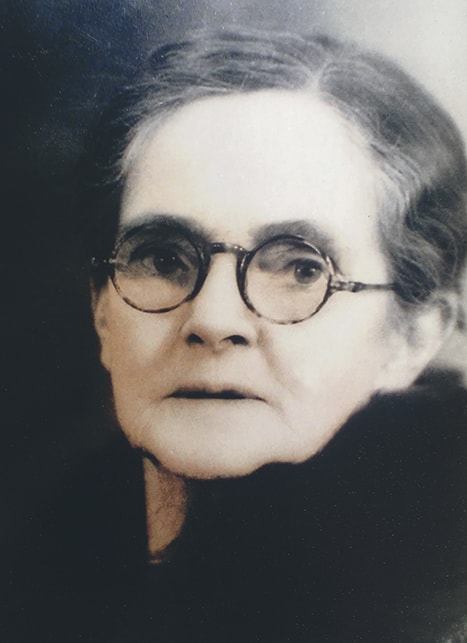

Ellen was made of stirring stuff. She packed up her children and walked all the way to Devonport, taking a job in a guesthouse. During their stay in that very guesthouse, Sydney and Ada Smallfield offered to employ Ellen’s daughter, Lily, as a ‘companion’ for Mrs Smallfield, who had no children of her own. Lily and her sister Olive refused to be separated and so the Smallfields took both children to their Puncheon Island residence. Olive became employed

with a Robinson family on Great Dog Island (known as Big Dog or Dog Island). Valentine was clearly very fond of both of his ‘adopted’ sisters, however he married Olive in 1916. Although much is known of Olive’s history, Valentine’s parentage and early childhood are a mystery.

Ken: I looked in online newspapers, just looking for station master, Railton, or Sheffield, or Launceston, because he, when he enlisted in World War I, gave his place of birth as Sheffield … And then he enlisted in World War II and he gave a different place of birth. But I think he was brought up by the Morids in Launceston.

Ken Willis, Melbourne, 2018

In 1966, Nana Willis and Uncle Bill Mills, her brother, visited our family, when we lived in Fenton Street, Devonport. I had my fifth birthday there. They talked about how they used to live in a guesthouse in that very street and they were incredulous that Max and his girls lived in the same street.

Ellen adopted a young fellow later herself. I see her there, stiff and still for her portrait with that young boy. She was wire-thin and sharp of jaw and mouth: a woman of grit. Her kids went off to the Furneaux Islands and between Hobart and the Furneaux they kept in touch. In Hobart Ellen was strident, publicly protective of herself in the face of Michael Mills’ duplicity.6 But she was in the Furneaux too. She died in Lady Barron in 1941, cared for by her son Henry, who we all knew as Uncle Bill. The islanders know him still, fondly, as Billie Mills.7

Ellen is buried at grave No14 at the Whitemark cemetery. It says plainly, incised in black weathered granite, ‘MOTHER’.8

Valentine – known as Pop or Val – and Olive – Nana Willis9 – became a well-known Furneaux couple. They lived the first years of their marriage on Cape Barren Island and eventually moved to Flinders Island (the largest of the Furneaux Group), where they lived in a cottage that once occupied the site of the Furneaux Tavern in Lady Barron. The family then moved to a site known as ‘up behind Tuck’s’ (Tuck Robinson) on Maynards Road. Val built a family home at Ranga, known also as The Forest, where they raised their nine children.

One of Dad’s cousins told me that Nana Willis would always tell her children to take the fight outside; to go outside and sort it out, to keep it out of the house.

Sally: Oh that was one of my favourite memories of Nana, she used to come and visit Mum and have coffee and Mum would stop work, because she was always working, didn’t often sit down knitting or anything like that, she was just busy all the time. Nana would come and so they’d sit, and they’d have a chat about everything that was going on, on the island, and I’d just sit there lapping it up and as long as I was quiet, I could stay there. If you started to make your presence felt it was ‘off you go and play’, but that was one of my favourite pastimes as a child, just sitting there listening.

Jane: It’s sort of part of that women’s circle somehow and pretending that you’re grown-up inside, somehow you’re privy to the grown-up conversation

Sally: I was quite young … and it was just so interesting to me.

Sally Fitzpatrick, Lindisfarne, 2018

Frances: Well we all knew her as Nana Willis.

Peter: Yeah, she was the most respected lady going around. Everyone called her Nana. She was just Nana to everyone.

Frances Claybrough and Peter Gavin, Lady Barron, 2018

The Smallfields and Ellen Mills ended up dwelling in a cottage, then called Malolo, on the corner of James [now Henwood] Street and Franklin Parade in Lady Barron. Phill (my husband) and I bought this cottage in 2018 and it is now called Mololo to honour a small spelling error of my father’s: he wrote it thus on the back of a photograph of the family at Mololo.

Val and Olive’s mutton-birding shed, the East End Hut on Big Dog Island in Franklin Sound, was home to the annual birding industry that formed an important part of the family’s island life for more than a hundred years.10

Mutton-birding was (and remains) a family affair. School holidays in the Furneaux Group used to be adjusted so that everyone, including the children, could be involved in the harvesting and preparation of the birds. Birding occurred annually from the end of March to the end of April, when the adult birds would leave their young in the burrows while they searched for food at sea.11 The tradition was handed down from generation to generation as the family gathered to share stories and work with one another. Those children who did not live in the Furneaux Group were often sent off to the islands every season to partake in the ritual. Members of the Furneaux community share fond memories and for most, barring a rare few, a fierce love of eating the bird itself remains.

Bruce Bensemann is a strappingly fit octogenarian and a fine raconteur of Furneaux tales and history.

Bruce: I used to be able to do four and a half birds a minute. Cut the head, cut the tail off, split it up the middle, open it up, take the insides out, turn it over, take the wings off. Frank Willis liked to stand for this work, I preferred to sit. Four and a half birds a minute. After you cut the head and the tail off … well Frank preferred to leave the head on because he said it saved his hands some protection, because the neck is still there. I cut the neck off first and then pick it up and cut the tail off, split it open and then open it up.

This mutton-bird they’ve got on Fisher Island, I reckon it’s gone by now, but it’s got a ring on its leg and the National Parks ranger searched for it in its thirtieth year, and sure enough, they recorded it coming back to Fisher Island and laying its thirtieth egg. One egg a year and it’s come back thirty times. And they don’t lay till they’re six.

Nina: Thirty, so it’s at least thirty-six years old! I didn’t think they could live that long.

Bruce: Yes, it laid thirty eggs.

Nina: How amazing! And considering how many of them die when they migrate down, that’s quite incredible that it survived, it must’ve had its route really well figured out.

Bruce: They travel in a big mob and of course the only time they touch land is here, when they nest. They live entirely on the sea for the rest of the journey and being a bird, they moult every year. They moult in two stages. They moult their tail feathers and wing feathers. At that stage they can’t fly, they just spend their time paddling on the water as they’re going across the equator where it’s nice and warm. They just paddle on the water. When the wing feathers and tail feathers grow, they fly and soar and moult their body feathers. Spend most of the time in the air. Mm, they’re a fantastic bird.

Nina Giblinwright and Bruce Bensemann, Shearwater, 2018

During 1995, Big Dog was given to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community in restitution; the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania holds its title.12 Descendants of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community (including those who once worked for the Mills-Willis family) now manage their own heritage and history, carrying out their traditional harvesting practices each year.

An ongoing lease was granted to Frank Willis to enable the family to continue its birding traditions. More recently, however, commercial harvesting of mutton-birds has been restricted to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community and commercial birding for the Willis family has almost ceased; it continues in the new families formed through marriage with Indigenous Tasmanians. There are several arms of the family who pursue amateur birding every year and while their experience has greatly changed, due to differing guidelines for amateur collection (for example, the use of long wooden spits is not permitted during amateur collection)13 they ensure the continuation of the family activity of the harvest, and the wonderful food.

Dingo is Damian Lowery, a north west coast man who is developing his mutton-birding family future. I met Damian on Big Dog; he heads there annually for the birding season with John Wells. He agreed to have a further chat sometime with me and Pete. We took a trip to Burnie and had a most fabulous conversation, in the Beach Hotel accompanied by a fantastic late 1970s soundtrack, about birding and island life and the pursuit of culture for his family.

Dingo: … one of the biggest, one of the most memorable things I ever experienced is we were all around there one day and we were sending them back and I wasn’t on the boat at that stage. Tim Maynard was driving the boat, boating them out, and there was a whole heap of us up in the rookery, there was Reggie, there was Terry Maynard, Aaron … there was a whole heap of ’em up there … and we got a hundred birds, or two hundred birds … one hundred and ninety-nine birds, and we didn’t have no spit … and there was a big ol’ marking post there. I said, ‘Oh, well, we put ’em on that.’ They said, ‘Oh fair enough’. Gone and got this marking post and we rubbed it up on the rock and sharpened it up a bit and drove it into the ground and put one hundred and ninety-nine on it! And we looked around and they said, ‘Well, who’s carrying it?’ I said, ‘I’m not carrying it! I’m not carrying it, my knee’s buggered.’ Bucky said, ‘My back’s buggered!’ and Aaron looked at me and he said, ‘Well I’m just not carrying it!’ and I said, ‘Well, I ain’t leaving ’em here!’ I said, ‘What if two or three of us get on and carry it?’ … ‘No, no, no, no!’ I said, ‘Well just put ’em on me then, you fellas lift ’em up and put ’em on me.’ And they lifted ’em up and put ’em on me, and I walked down right from the top of the hill right down to the beach and onto the boat with one hundred and ninety-six, cos three fell off [laughter], and I always say to Timmy, cos he’s a real big fellow, I always say to him, ‘I beat your record mate’. He said, ‘I’ll beat it.’ I said, ‘Well, you need a marking post mate!’ and he goes, ‘No, I’m taking a metal pole.’ Yeah, so no, ‘You won’t be able to carry it I don’t reckon.’ ‘Put it on me, I’ll carry it.’ And when I stepped on the boat it went off like a shotgun over me back, and Timmy took it back to Tanya and John’s shed. Each half of the spit took two men to lift it out of the boat, each half, so it was four men and we put it back together and took a photo of it, one of the biggest loads, well the biggest load I’ve ever carried and the biggest load I’ve ever known anyone else to carry …

Dingo Lowery, Burnie, 2018

Pete Hay, a Tasmanian geographer and poet produced a series of poems and prose writings in response to the island experiences we shared.

I use specific colours and tones in the painterly differentiation of three family generations. Nana and Pop are shiny with sienna and ochre, deepened with their earth, whereas their children are more brightly coloured and more actively posed. They are the deeply revered generation of the family. My father’s generation is yellowed and muted, placed a little further away from the audience as memento mori. This generation will vanish. We know them, all of them. The cultural and economic contribution provided by the two previous generations is the foundation for this work.

This book contains my honouring of my family’s mutton-birding island lives. It also recognises and honours the change that we have had to come to terms with.

Instruction on Birding

It helps if you started when you were eight, having stowed away for Three Hummock in your father’s van.

If you were brought up rough, living on wallaby, muttonbird.

If you’ve birded Big Dog these past twenty years.

That you’re one of those who pick it up real quick. Lots can’t. Some young fellas get it, but some aren’t interested.

If you’re a natural you can get down in the tussocks, shut your eyes, hear what’s going on down the holes.

You have to know how to work the rookery properly. If water’s got in, or if they’ve been down the hole too long, the skins are too soft and you can’t pluck ’em.

You have to leave there till the chicks start coming up and their skin hardens. Hard to teach young blokes that – they’re too impatient.

Too much krill is gone from the ocean. It’s a food chain thing. Instead of resting up and eating easy the birds are fighting for food.

It’s such a strong fighting bird, a storm bird, it can handle any amount of shit weather. But there has to be food.

You have to learn to care for the land.

Have dads and uncles to teach you.