On these islands the bush is shaped by the wind, leaning west to east, whipped to submission. Here, on Flinders, the largest island in the archipelago, is an islandscape simultaneously dramatic and drear, epic here, saturnine there.

When you retreat from the coast, anyway. Lashed by a southern turbulence of water and a lunatic scream of wind, there is no ambiguity over the drama of the coast, on any of the islands. Stand on the cliffs, the beaches, drag salt-laden air into your lungs, sink below a hugeness of sky, and you shrink into a smallness within the greater scheme of things, humbled rather than diminished, attaining a true, modestly human context.

You want to know the humans who first came here, and their motives. You know that Aboriginal people lived on and used the islands when they weren’t islands, but part of the isthmus connecting what are now the mainlands of Australia and Tasmania. You understand, though, that from the stabilisation of current sea levels to the coming of Europeans to this part of the world there were no humans in what is now the Furneaux Group, and that the next inhabitants were a mix of semi-marooned sealers originally working for Sydney merchants, shipwreck survivors who stayed, runaway convicts and the Aboriginal women from the north-east Tasmanian mainland who were captured and brought here. These people lived beyond the fringes of the law, and there are whispers of piracy, wrecking. The names of the sealers persist in the islands to this day, and for many decades there was a simultaneity between the descriptors ‘Aboriginal’ and ‘Islander’. Aboriginality in Tasmania survived predominantly, perhaps exclusively, through the offspring of the sealer-Aboriginal liaisons. And it was here, at Wybalenna on Flinders Island, that the doomed ‘Friendly Mission’ of George Augustus Robinson stuttered to its tragic conclusion.

In later, less turbulent times, people arrived to fish and farm. Their imprint upon the land was, in essence, a taming one, but they had to work within the turmoil and drama of the archipelago’s human history, and they had to work with the turmoil and drama of the archipelago’s geography.

One of these families was that of Valentine and Olive Willis, along with all the families that their generations of offspring (tumbling through a century and more) married into, and who married into them. As is the genealogical way, there are Willises still in the islands, and Willises who are not in the islands, and these are outnumbered by the Willises who no longer carry that surname, and who are also to be found in the islands, and not in the islands. Some of those not in the islands yearn for their lost birthright. Some, a small few, are pleased to be shot of it.

On Flinders Island the Willises farmed and fished, and still they farm and fish. They also ‘birded’, holding a long-term lease on a mutton-bird shed on Big Dog Island (officially ‘Great Dog Island’). Willis lease rights were ceded when the island became exclusively Aboriginal in 1995 following a successful land-rights claim, but there is still a Willis shed on Big Dog (albeit not Val Willis’s original shed) by virtue of a marriage between an Aboriginal woman (Jo) and one of Val Willis’s grandsons (Charles). Farmers, fishers, birders. And then there is one Willis, now living in Hobart and with a different surname, who is an artist. This is Jane Giblin, painter, lithographer, drawer, printmaker, photographer.

Olive and Valentine are my great-grandparents. I knew only my great- grandmother. Both Olive and Valentine were pivotal in the care of my father when he was a toddler. This is a love that has infused my life.

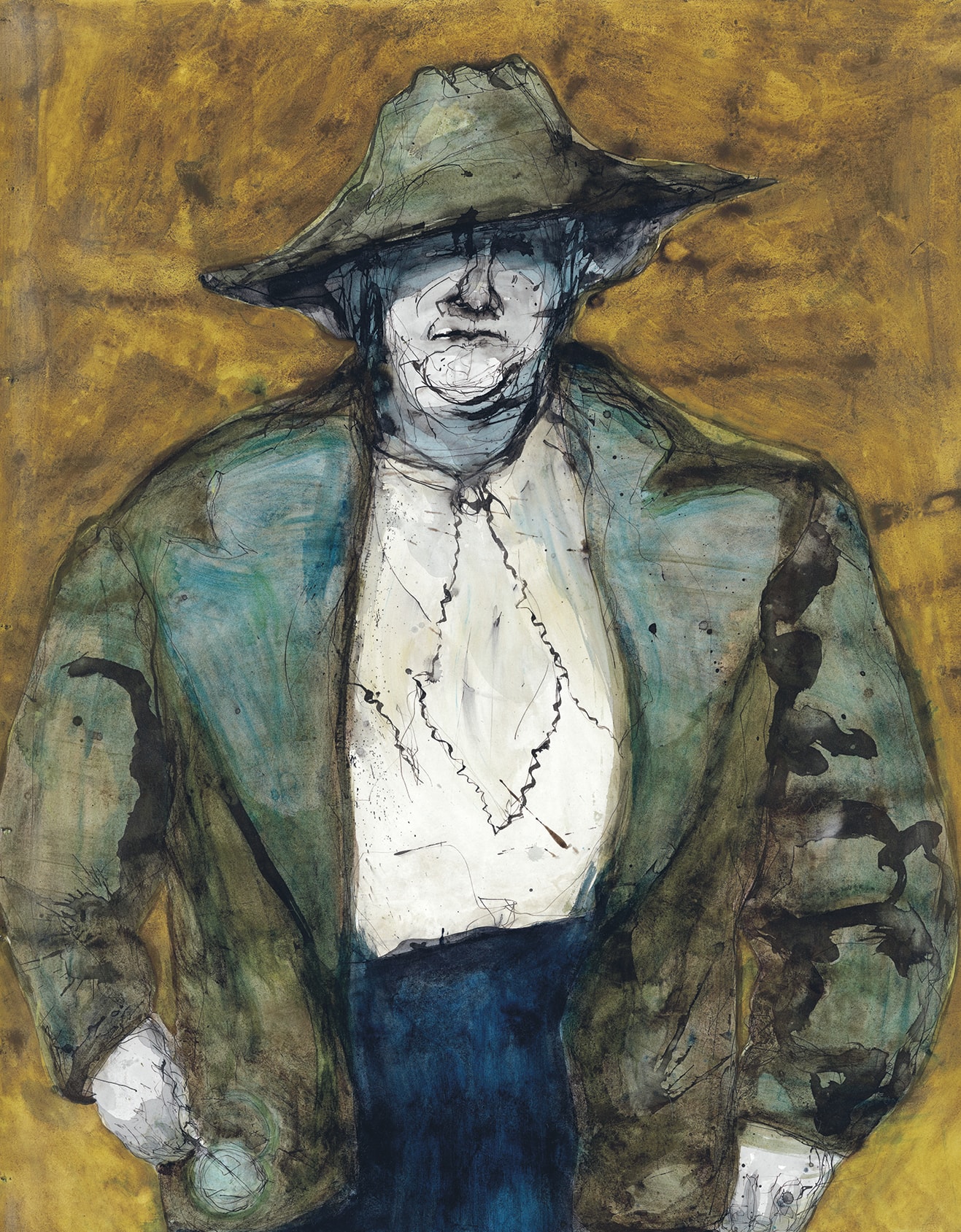

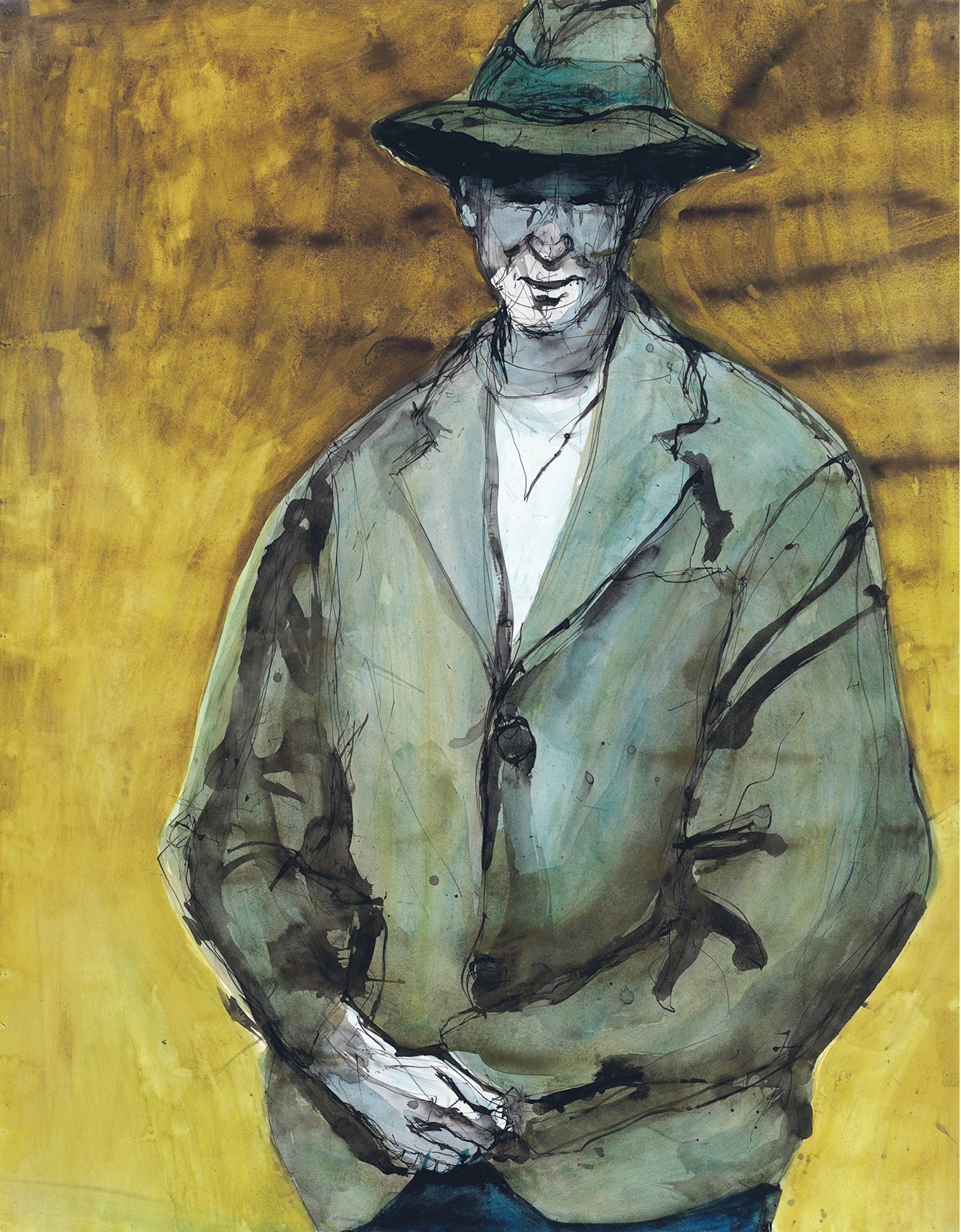

Jane’s art is bold and expressive, raw and confronting. Whether her medium is pigment, paint, ink or pen, she works in hard, strong strokes, pouring onto paper her anguished but confident soul. Her style is distinctly her own, instantly recognisable and perfectly suited to her project.

In I Shed My Skin Jane seeks to explicate the nature of life and work in an isolated island community. She wants to say something about the unique nature of islandness, about isolation, about place and its claims on our emotional attachments, and about the import of place-specific histories. Identity – communal identity, personal identity – are to be found at the potent point where geography and history intersect. These are generalised matters of great significance – indeed, Jane herself has written that she seeks insight into ‘this scattered island context, as a microcosm of many regional communities in Tasmania and mainland Australia’. But it is also of significance that the islands of which she writes are the context within which her own family stories have unfolded. She seeks explication of the general in the particular, and the particular in the general. This is a project that no-one else could have undertaken in precisely the same way, because Jane is who she is, and her islands are what they are. Her art, Andrew Harper has written (reviewing an earlier show for TasWeekend), ‘is ultimately personal and singular: her influence is her world, the history she knows, and how she investigates it’.

In one sense, this project is intensely genealogical. That alone establishes particularity, because any family is inevitably unique unto itself. And the individual members of this family, as Jane has lovingly portrayed them here, are each themselves unique items of island – or ex-island – life. One hundred years and five generations of a single family and their farming, fishing and birding activities – can you get from such particularity to generalised observation about family, about work, about place, about time and change, about land? And, specifically, can you do so through the medium of visual art? This is the hinge around which I Shed My Skin swings. And it is not a matter I intend to resolve – it is up to the individual viewer of this dramatic artwork – big, vivid portraits in pigment and smaller, detailed land-specific lithographs – to come to their own conclusion.

It is certainly the case that the islands of the Furneaux Group display characteristics that islands elsewhere replicate. Foremost among these are ecological factors. Island ecologies are both rich and differentiated – and vulnerable, vulnerability being a consequence of each island’s biological containment. To be girt by sea is to be trapped by sea, for there is no escape corridor available to species when they come under stress. Avian species, it might be thought, are excepted, for they can spread their wings and fly away. Not so – more than 90% of bird extinctions, historically, have occurred on small islands (about half of mammalian extinctions have also taken place on islands). They are locked in, then. On islands they struggle and on islands they die. The same insular stresses that are responsible for this sorry state of affairs globally also pertain to the islands of the Furneaux Group.

As it is for ecology, so it is for culture. Each of the world’s islands has experienced its unique human history, but it is possible to broadly generalise these histories. Islanders tend to be more culturally and politically conservative, to exhibit lower social and economic dynamism, than is the case with mainlanders.

They also tend to be more resilient, versatile and resourceful. They are ‘can-do’ people. They tend to be more place-attached – even when they move away, in their inner selves they carry their island with them.

But these are the grossest of generalities. What is far more significant are the histories specific to each island, and this specificity qualifies the extent to which generalisation can be sustained. So it is with the islands of the Furneaux Group. Nowhere in Tasmania is the issue of race relations as concentrated, as distilled, as it is in Flinders Island, Cape Barren Island and the islands of the shearwater rookeries. Jane meets this history head on. The only condition determining the subjects of her lithographic and photographic art is that there had to be a family connection. For this reason, there is no artistic engagement with Wybalenna. On the other hand, the persistent whispers that the Interstate Hotel at Whitemark contained a cramped ‘lounge’ for Aboriginal drinkers, they being barred from the rest of the pub, is tackled four-square. Others would shy away from such a theme – there are, after all, those who deny that the ‘Snake Pit’ ever existed. For Jane that would be a betrayal of her artistic integrity.

There are pockets of deep resentment in Jane’s extended family, stemming largely from their exclusion from the rookeries after generations of birding, following the success of the land-rights claims in the 1990s. Others, though, concede that the land-rights claims were justified. Jane is in this camp, but she tries to do right by all her family through the democratic depictions of her art. This has not been easy, and one of my points of admiration of Jane and her art is that she has not sought to elide this tension, the potentially disastrous consequences of incorporating it in the project notwithstanding.

Is there anything distinctive about family life on islands? I think there is. People on islands experienced a heightened, a concentrated, sense of place. This is a near-inevitable consequence of the hard boundary that the shoreline represents. Families grow and age, often through several generations, knowing that potent and defining island identity. There is no escaping a pronounced island psychology. For some this is very satisfying, providing life with meaning and comfort; for others it is stultifying, a psychological entrapment. Some will yearn to leave, though this is never easy, for it is not simply a matter of throwing a suitcase in the boot and driving away. It is a profound, logistically demanding decision and many who take that decision are thereafter deeply conflicted. They may, as a consequence, eventually return, or they may opt for precisely the opposite and never return, a yearning for an idealised castle-in-the-sky (so to speak) having substituted for the real thing.

I say this with a great deal of confidence, though the truth is that island scholarship has little to say about island-specific family dynamics. Solitude, a heightened sense of isolation (and, paradoxically, mutualism), social conservatism, an enhanced place attachment – these are among the better-known tropes of islandness. But we know less about the consequences of these and other characteristics of island living for family life. Jane has written of her project that she wants to see how ‘an isolated geography encourages traditions associated with survival and environment’. That she has chosen to do this through the prism of family, her own family specifically, seems to me conceptually inspired. As island economies, island demographies, island technologies and island ecologies change, so do ways of island living and family practices evolve. Jane sets out to ‘explore the stories of lost and changing communities, emanating from my own [Jane’s] family connections, who flourished in the Furneaux Islands. [I] seek to know who those people were, through many-layered narratives, often of the same events, and celebrate the development and change being experienced in the island community.’

The meanings encoded in art are ineffable. They ask a great deal of the viewer’s willingness and capacity for thoughtful engagement. That is the task ahead of us now. Jane’s family portraits are powerfully wrought, her subjects characterful, living embodiments of island life. Her palette is understated, her mode of layering pigments strong, deft and purposeful. Through parents and grandparents, aunts and uncles, island essences emerge. And in the ‘etched traceries’ of her lithographs, the island ground through which they moved is made palpable, sometimes merely hinted at, sometimes bluntly tangible. And here, too, there are people – family members of Jane’s and later generations (and others), the bond between them and Jane’s chosen elements of country there for the reading.

It is this component of I Shed My Skin that is the focus of my own involvement. I hope I have done Jane and her project proud – certain it is that I immensely enjoyed the challenge. The project is ambitious – I could even say daring – and she has realised it effortlessly (the impression is that it has been effortless – doubtless that wasn’t actually the case!) It is artistically bold and conceptually significant. Jane has produced a body of work that befits the boldness of the undertaking.

Pete Hay

This essay was originally published in the exhibition catalogue I Shed My Skin, A Furneaux Islands Story, 2019